Tarisai Mutangi

LLD (Pretoria) LLM (Pretoria) LLB (Zimbabwe)

Head of Department, Postgraduate Legal Programmes, Faculty of Law, University of Zimbabwe

Volume 54 2021 pp 512-532

Download Article in PDF

SUMMARY

This paper primarily focuses on revealing the status of implementation of human rights decisions of the Community Court of Justice of the Economic Community of West African States (ECCJ). It acknowledges that dialogue on human rights has ventured into an era where more research and scholarship ought to be focused on implementation of human rights commitments including decisions of human rights tribunals. Dedicated to the ECCJ, the principal legal organ of the Economic Community for West African States (ECOWAS), the paper traces the evolution of the Court in the early days of restricted human rights competence to a time of its affirmation through ECOWAS legislative instruments. Utilising the implementation assessment framework used by the Committee of Ministers (CoM), the assessment is based on a sample of 75 cases covering all categories of human rights, but full discussion was limited to a few significant decisions that demonstrate the different aspects of this analysis. The major finding was that non-implementation of ECCJ decisions is a growing concern in ECOWAS. A few cases have achieved full compliance yet the majority were either partially implemented or not at all. The paper also found that there is a huge information gap between real time status on implementation on the ground and that which is perceived. Accordingly, the paper concludes by inviting more empirical research that is informed by the actual actors and decision-makers at the national level for a better understanding of the dynamics at play in each context. However, the paper found unique features of the ECOWAS human rights architecture including advanced legal framework on implementation; an elaborate sanction regime for non-compliance; full compliance in monetary-based orders; and clarity of remedial orders among others. These are recommended for other sub-regional systems.

1 Introduction

The discourse on human rights in Africa, including at the sub-regional level known as Regional Economic Communities (RECs) continues to shift from the standard-setting phase (norm-creation) to implementation of human rights standards.1 The norm-creation was an era primarily characterised by the adoption of treaties and protocols, which provide for normative content of fundamental human rights and freedoms. The shift is to a phase of dialogue on implementation of state party obligations or commitments that arose on ratification of these instruments (norm-enforcement). This is because ‘[d]efining human rights is not enough; measures must be taken to ensure that they are respected, promoted and fulfilled’.2 These commitments exist in the form of specific rights and freedoms drawn from treaties; concluding observations issued under the state party reporting procedure or those in the aftermath of fact-finding missions; and those arising from decisions or judgments of tribunals or courts − the subject matter of this article.

On their part, treaties establish institutions and vest in them the competence to monitor or supervise implementation by member states, of human rights commitments as enshrined in those instruments. Supervision of implementation is critical. Rather than being seen in the negative sense as predicting non-compliance with obligations, it should be positively interpreted as an opportunity for supervisory institutions to assess states when implementing their commitments. For instance, in their decisions, human rights tribunals or courts essentially guide the execution of their orders by couching them in a way that specifies, as far as possible, the measures that a state should adopt in order to fully comply with the decision. In order to induce compliance, these treaties often establish an enforcement framework or mechanism and its modalities of operation clarified therein.

Notwithstanding the presence of enforcement frameworks in several treaties, non-compliance or non-implementation of decisions of human rights courts has become a concern throughout the known human rights systems. States struggle to implement court decisions. Scholarship and research has identified a number of reasons behind this phenomenon many of which will be discussed in this paper in respect of the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS).3 These reasons include factors pertaining to the state party concerned; the articulation of remedies in the remedial order; the role played by the court rendering the decision; and the role of policy organs of the human rights system concerned, among others.

This paper is an extract of a baseline survey report on the state of implementation of decisions of the Community Court of Justice of the Economic Community of West African States (ECCJ).4 The Pan-African Lawyers Union (PALU) in partnership with the Raoul Wallenberg Institute of Human Rights and Humanitarian Law (RWI) conducted the survey under the Africa Regional Programme focussing on implementation of human rights commitments in Africa. The survey represents a genuine attempt to take stock of ECCJ human rights related decisions and record the status of compliance or implementation of these decisions in that region.

Building on the survey, the paper first explores the evolution of human rights adjudication in the ECOWAS in the context of the formation and operationalisation of the ECCJ. Secondly, it examines the human rights architecture of the ECOWAS as reflected in its legal and institutional framework. Thirdly, the paper analyses the legal framework on implementation of decisions of the court and the mechanisms developed to oversee this process. Fourthly, the paper assesses the status of implementation of selected decisions of the ECCJ across the sub-region. Cursory references are also made to other decisions for illustration purposes.

As to the brief history of the ECOWAS, sixteen West African states adopted the ECOWAS Treaty in 1975, which established the ECOWAS as an inter-governmental and sub-regional economic bloc or community organisation. As a typical REC focused on economic integration, human rights was not a top priority of the ECOWAS agenda. However, a combination of regional and international developments triggered a rethink of priority areas also leading to the adoption of instruments that led to prioritisation of human rights. For instance, from 1975 to the 1990s the occurrence of events such as armed conflicts among countries in the region including Liberia and Sierra Leone, falling socio-economic standards and the wave of democratisation in Africa, triggered this prioritisation. In particular, the ECOMOG involvement in the Liberia conflict nudged the ECOWAS to focus more on security and human rights. In order to appropriately place itself to deal with the emerging challenges, the ECOWAS revised its founding Treaty.

The 1975 Treaty was revised in 1993 (Revised Treaty) and provided for the establishment of the ECCJ, but detailed provisions on its competence and design are outlined in the 1991 Protocol Relating to the Community Court of Justice (1991 Court Protocol).5 The Revised Treaty reiterates the “over-riding need to encourage, foster, and accelerate the economic and social development of our States in order to improve the living standards of our peoples”. In article 4(g) of the Revised Treaty, member states are bound by the ECOWAS founding principles that include “recognition, promotion and protection of human and peoples’ rights in accordance with the provisions of the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights”. The mention of the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights (African Charter) put to rest any debate about the lack of a normative human rights framework until that time. It also elevated human rights norms in ECOWAS to a standard relative to the African Union (AU). As will be discussed later, the absence of a normative human rights framework within ECOWAS sparked heated debate about the ECCJ’s competence to deal with human rights complaints filed by individuals.

2 The Economic Community Court of Justice (ECCJ)

Article 6(1)(e) of the Revised Treaty read together with article 15 establishes the ECOWAS Community Court of Justice (ECCJ) as the principal judicial arm of the Community. The Revised Treaty deferred the details on the operation of the Court to the 1991 Protocol on the Community Court of Justice (1991 Court Protocol) adopted by the ECOWAS high contracting parties. Seven judges used to sit on the Court, but these have been reduced to five since 2018, each serving a five-year term renewable once. No two judges can be nationals of the same state and the minimum age for appointment is forty while those above 60 are not eligible for appointment as retirement age is officially 65 years of age.6

The role of the ECCJ is to perform judicial functions such as interpretation and enforcing community law. For the purpose of effective execution of its mandate, article 15(3) guarantees its independence from member states and ECOWAS institutions. Further, its decisions are binding on “Member States, the Institutions of the Community and on individuals and corporate bodies”.7

Perhaps leveraging on the ECOWAS institutional reform process, in 2005, the ECOWAS adopted a supplementary protocol to amend the 1991 Protocol on the ECCJ.8 The ECOWAS adopted the 2005 Supplementary Protocol Amending the Preamble and Articles 1, 2, 9, and 30 of the 1991 Protocol Relating to the Community Court of Justice (2005 Supplementary Court Protocol). Article 3 provides for the composition and the functions thereof.9 One of the high points of the 2005 Additional Protocol was the specific conferment of a human rights mandate on the Court. Article 9(4) of the Additional Protocol now provides that “the Court has jurisdiction to determine cases of violation of human rights that occur in any Member State”. This provision assumes personal jurisdiction of the Court over all members of the ECOWAS without need for further requirements.

A new article 24 of the amended 1991 Court Protocol exclusively regulates the enforcement of the Court decisions. It echoes article 15 of the 1993 Revised Treaty in providing that decisions of the ECCJ are “binding”.10 The provisions further legislate that these decisions are executed “in the form of a writ of execution ... according to the rules of civil procedure of that Member State”. On that basis, Adjolohoun concludes that national authorities only need to verify that the writ was issued by the ECCJ for purposes of implementation without need for further requirements.11 On their part, states are required to “determine the competent national authority for the purpose of receipt and processing of execution and notify the Court accordingly”. These are national focal points for purposes of receipt and oversight of execution of court decisions at national level.

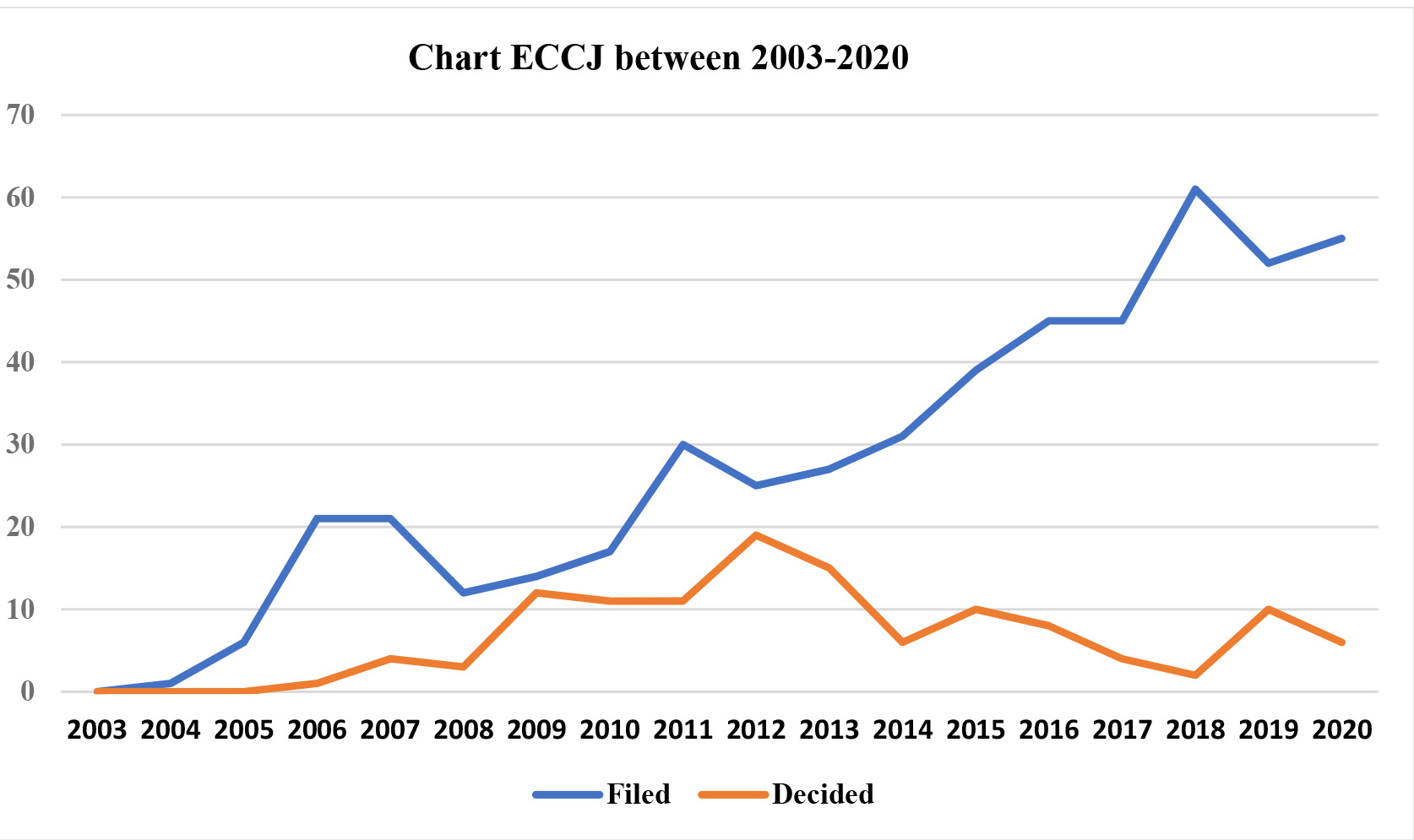

The ECCJ became operational in December 2000. To date, about 496 cases have been filed before the ECCJ.12 During this period, the Court delivered 261 judgments since 2003. In 2018, about 60 new cases were filed with the ECCJ, marking the highest number of cases ever filed in a single year in the Court’s history. The vast majority of the cases that were filed are human rights cases. Some of the judgments the Court has delivered have been ground breaking such as those relating to slavery, enforced disappearance, free and compulsory education, and the domestic prosecution of former Chadian President Hissène Habré in Senegal. To this end, the ECCJ has been making a substantial contribution to human rights jurisprudence on the continent.

2 1 The human rights-related jurisdiction of the ECCJ

As indicated above, the jurisdiction of the ECCJ was clearly one that originally did not include an express provision on human rights related competence. This lacuna was due to the absence of a protocol or any other normative human rights instrument adopted by the ECOWAS until its recognition of the African Charter in the Revised Treaty and the express conferment of a human rights mandate to the Court in terms of the amended article 9(4) of the 1991 Court Protocol. The absence of a normative framework could also have been partly a result of the slow acceptance by RECs of the human rights agenda over and above the traditional socio-economic integration.13 However, in spite of a clear human rights mandate, scholarship analysing the Court’s work approaches this development with caution. Ebobrah submits that notwithstanding stakeholders taking advantage of the expanded jurisdiction of the Court, and the “ECCJ has warmed up to its new mandate; uncertainty still trails the functioning of the court in relation to its human rights mandate”.14 The author cites lack of foundational legitimacy for human rights within the ECOWAS, the absence of an ECOWAS-specific protocol on human rights and the practice of the Court are grounds for such “uncertainty”.

Flowing from the 2005 Supplementary Court Protocol, there is a new competence of the Court to adjudicate on “the failure by Member States to honour their obligations under the Treaty, Conventions and Protocols, regulations, directives, or decisions of ECOWAS”.15 Such a jurisdictional issue is relevant to the discussion on implementation of ECCJ decisions. The provision admits an interpretation that a member state stands to be brought before the Court for failing to honour obligations. By extension, this paper argues that failure by a member state to implement a human rights related decision of the ECCJ is in itself failure to “honor obligations” or commitments. Such failure invokes the jurisdiction of the ECCJ to deal with the specific issue of “failure to honour” obligations under the decision of the ECCJ. In other words, the ECCJ has competence to preside over cases where a litigant returns to the Court to report a member state for failing to implement an earlier decision by the same Court. However, this jurisdictional competence will be fully discussed as an enforcement mechanism built in the ECOWAS human rights system.

2 2 The Court’s evolution and progress

The human rights mandate of the ECCJ has a long history dating back to the very first case of in Olajide Afolabi v Nigeria, which raised the issue of individual access to the Court prior to the 1993 Revised Treaty.16 Olajide Afolabi was a Nigerian trader who had entered into a contract to purchase goods in Benin. Afolabi could not complete the transaction because Nigeria unilaterally closed the border between the two countries. He filed suit with the ECOWAS Court, alleging that the border closure violated the right to free movement of persons and goods. Nigeria challenged the Court’s jurisdiction and Afolabi’s legal standing, arguing that the 1991 Protocol did not authorise private parties to litigate before the Court. Afolabi countered by invoking a Protocol provision stating that a “Member State may, on behalf of its nationals, institute proceedings against another member State”.17 The Court rejected this and other arguments Afolabi raised and dismissed the case. The Court, however, acknowledged that Afolabi’s case raised “a serious claim touching on free movement and free movement of goods”, but held that it was necessary to have an ECOWAS legal instrument expressly granting the Court jurisdiction.

Commentators argued for some time that there was sufficient legal framework within the ECOWAS community law to ground the Court’s jurisdiction, but the “ECCJ shied away from such judicial activism and gave room for legislative endowment of competence in the field of human rights” with the adoption of the 1991 Protocol confirming this nature of jurisdiction.18 This made the human rights mandate “legislature-driven” as opposed to court-driven as was the case in East Africa and Southern Africa.19

At the creation of the Court, the Court had the competence to receive cases relating to disputes between ECOWAS member states, or between member states and ECOWAS institutions (contentious jurisdiction). The Court could also give advisory opinions on any matter that required interpretation of the Community text (advisory jurisdiction). As already stated above, the 2005 Supplementary Protocol expanded the jurisdiction of the ECCJ to include the competence to adjudicate human rights cases. Article 3(4) of the Supplementary Protocol provides that “the Court has jurisdiction to determine case[s] of violation of human rights that occur in any Member State”.

Article 4 of the Supplementary Protocol inserted a new Article 10 into the 1991 Court Protocol, which regulates the critical issue of access to the Court. Over and above members of the ECOWAS and its institutions who traditionally had access to the Court, the provision now provides that access to the ECCJ is open to, amongst others, individuals who are seeking relief for violation of their rights due to the conduct of a Community official as well as individuals seeking remedies for violation of their human rights.20 It accordingly, puts to rest doubts and concerns aroused by the Court’s decision in the Afolabi case pertaining to the presence of individual competence within the ECOWAS human rights architecture.

The issue of access to the ECCJ is of interest as the Court’s practice of excluding the need for exhaustion of domestic remedies before filing a complaint with the Court is rare and, therefore, prominent.21 This means that a victim of human rights violations has no legal obligation to approach national courts for the resolution of the dispute before they qualify to lodge a complaint with the ECCJ. The non-application of the exhaustion of local remedies rule is by virtue of its omission from the constitutive instruments of the ECCJ. The omission of this requirement from the 1991 Court Protocol and again in the 2005 Supplementary Protocol would accept that conclusion. Article 10(1)(d) of the amended 1991 Court Protocol bears only two requirements from an applicant. Firstly, the author of the complaint should not be anonymous, and secondly, the matter complained about should not be pending for adjudication before another international mechanism.

2 3 Conceptualising implementation, execution and compliance

The focus of this paper is assessing the state of implementation by states of the human rights-related judgments of the ECCJ. Accordingly, it is necessary to deal with key terms to be used in the discussions. “Implementation” and “execution” of decisions pertain to the process when a state adopts measures necessary to give effect to each decision of the court. These measures may be outlined in the judgments, or where they are not, the state chooses such as those with a bearing on executing the decision. The right to choose is part of the exercise of state sovereignty in international law. Once these measures have been fully adopted, the state concerned reaches a state of execution or compliance. In this sense, “compliance” is an outcome of implementation (process). It is measurable hence; there could be cases of “non-compliance”, “partial compliance” or “compliance” as in full compliance.22 Compliance is achieved through a “deliberate”, and not a “serendipitous compliance” approach.23 States have to take deliberate actions in order to fully execute any judgments against them. This is because compliance “is a matter of state choice” that strongly draws from the political will of a particular state to adopt measures as are necessary to execute decisions of the Court.24

As scholarship and research continues to grow around the issue of compliance with decisions of international human rights courts or tribunals such as the ECCJ, this area of study is incrementally catching the attention of scholars and practitioners. Consequently, compliance has not been spared the scholarly controversy concerning its definition in relation to states’ international obligations. Some scholars have attempted to enhance the understanding of compliance by examining how and why nations behave the way they do in relation to international legal obligations.25 In answering this question, other scholars and thinkers have postulated theories to explain the phenomenon of why states sometimes decide to live up to their human rights obligations.26 In so doing, Koh mentioned virtually every stakeholder who should participate in the compliance process, and the specific roles they ought to play.27 Through the transnational legal theory, Koh made the proposition that national and international actors exert pressure on the state concerned to comply with its obligations. The intervention of each stakeholder is based on their functions and methods of work. While national actors may raise the state’s political cost at that level, international stakeholders have a different dynamic where for instance, they name and shame the state in international foras thereby inducing compliance. However, it is the collective efforts of both national and international stakeholders to which compliance is credited.28

The thesis of this paper on the status of implementation of decisions of the ECCJ is that the assessment is an audit of measures states have taken to execute the decisions. For the compliance outcome to be achieved, the measures states adopt in the aftermath of a human rights judgment are acceptable where they have achieved the purpose for reparations as articulated by the International Court of Justice (ICJ) in the Chorzow Factory case, namely:

[R]eparation must, as far as possible, wipe-out all the consequences of the illegal act and re-establishes the situation, which would, in all probability, have existed if that act had not been committed. Restitution in kind, or, if this is not possible, payment of a sum corresponding to the value which a restitution in kind would bear; the award, if need be, of damages for loss sustained which would not be covered by restitution in kind or payment in place of it - such are the principles which should serve to determine the amount of compensation due for an act contrary to international law. 29

The above quote summarises what compliance with a human rights judgment should achieve. The element of “reasonable performance”, say in paying reparations, has to defend itself by passing the test of whether such performance achieved the effect of wiping away the consequences of an illegal act and achieved re-establishment of the situation which ought to have obtained had it not been for the violation.30 Compliance with a judgment would manifest itself where a state has, as far as possible, taken all measures contemplated in the judgment with the effect of extinguishing all the negative consequences of the violation putting the applicant in a position he or she would have been had there been no violation. Where negative consequences remain evident after the so-called “reasonable performance”, then such compliance is not the one envisaged by the principles briefly stated above. It is the extinguishing effect of performance that embodies the “good faith” element by clearly avoiding “superficial implementation” or “circumvention” thereof. The view of this paper is that implementation falling short of the “extinguishing” effect is insufficient and ineffective to qualify as compliance. Accordingly, it is submitted that “performance in terms of the judgment” is the criteria for assessing implementation. However, there are cases where it is no longer possible to “wipe-out” all consequences, in which case a substituted remedy is awarded. For instance, in the case of violation of the right to life, no remedy can restore the life, yet the court may award damages as compensation.

Furthermore, full compliance means the state has to take measures as are necessary to terminate situations of continuing violation and guarantee non-repetition by adopting general measures over and above individual measures.31 This is logical. Unless continuing violations are terminated decisively and non-recurrence guaranteed, restitution as developed in the Chorzow Factory case cannot be achieved. The consequences of illegality will not only remain, but also continue to accumulate. Re-establishment of the ideal situation cannot be imagined. Termination of violation and guaranteeing non-repetition is the golden thread that runs throughout the remedial philosophy of all the regional human rights systems, and is at the core of the conceptualisation of remedies.

As for assessing implementation of ECCJ human rights decisions, this paper utilised the criteria adopted for use by the Committee of Ministers (CoM) of the Council of Europe (CoE).32 In supervising execution of the decisions of the European Court of Human Rights, the CoE utilises the following criteria:

- Whether any “just satisfaction” (often a combination of pecuniary losses, non-pecuniary losses, legal fees, and interest payments) awarded by the court has been paid;

- Whether individual measures have been taken to ensure that the violation in question has ceased and restitutio in integrum achieved − in other words, that the injured party is restored, to the extent possible, to the same situation he or she enjoyed prior to the violation;

- Whether general measures have been adopted, so as to prevent “new violations similar to that or those found, putting an end to continuing violations”.33

The criteria above represent a methodical approach to assessing status of implementation of each court decision. It is criteria that defies regions or human rights systems in that it inherently interrogates progress respondent states have made in executing judgments of the court in which they were parties. This position holds true in the European human rights systems as it does in Africa at large and the ECOWAS Community in particular. Accordingly, the assessment to follow will interrogate three aspects of implementation; first, whether the state has paid any moneys ordered by the ECCJ; second, whether the state has taken measures to deal with personal circumstances of the applicant as directed by the Court; and finally, whether the state has taken any measures to guarantee non-recurrence of similar violations. Complete answers to these issues would, in each case, determine the status of implementation of decisions of the ECCJ.

3 Findings on the status of implementation of ECCJ decisions

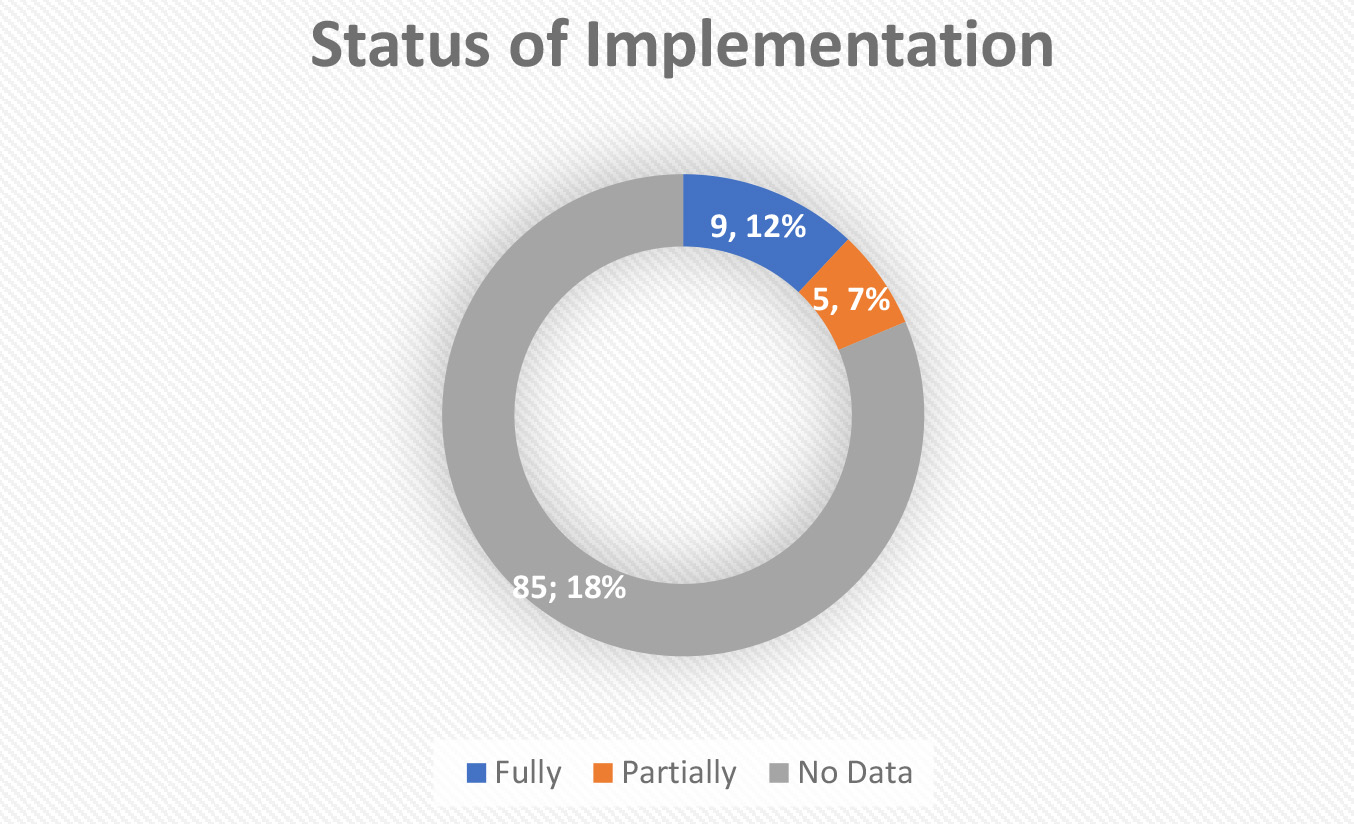

Figure 2 below contains information on decisions rendered by the ECCJ and the status of their implementation, among other useful information. While the key objective is to show the status of implementation of these decisions, the information is also useful to the extent that it enables readers to conduct further analysis such as the type of disputes whose decisions are more likely to be implemented, the time-frame it took to implement the decision from the time it was rendered, among other further and deeper analysis. However, the terms of reference that guided the production of the data presented in Figure 2 did not go as far as prodding the extent to which factors affecting compliance as discussed above apply in each particular case. To this end, the data points to opportunities for further research in order to have a comprehensive understanding of implementation patterns in the ECOWAS even in relation to other courts such as the East African Court of Justice (EACJ) and the African Court as discussed in other parts of this publication.

The ECCJ has so far issued about 75 decisions under its human rights mandate.34 Of these, less than half have been implemented, that is fully or partially. Although this rate is rather high by comparative standards, non-compliance with ECCJ decisions is still regarded as a challenge in the ECOWAS.35 Perhaps this explains the Court adopting new methods of work through judicial monitoring to improve implementation of its decisions.

Figure 2: Status of implementation of human rights decisions

Source: Extract from PALU Baseline Survey on Implementation of ECCJ Decisions

Figure 2 above is an extrapolation from the baseline survey conducted to establish status of implementation of human rights decisions of the ECCJ. While the data may not fully represent the state of affairs until it is triangulated, it suggests a few discussion points in the context of implementation.

First, it makes the point that the ECCJ largely remains a court primarily dealing with disputes that are socio-economic in nature with human rights-related disputes tracking behind. This trend could be historical in that it was only in 1993 and 2005 when the ECOWAS Treaty and Court Protocol were respectively revised. The revision formally introduced and affirmed the human rights mandate of the Court. The number of human rights cases has steadily increased since then, but the larger part of the Court’s jurisdiction illustrates that Community law continues to dominate.

Second, cases of full implementation demonstrate ECOWAS member states desire to support the work of the bloc’s judicial arm. It also represents a fair assessment of recognition of the legitimacy and the Court’s authority in the Community. Nevertheless, reasons for the degree of implementation may vary from state to state. For instance, Niger is one of the states with a near 100 per cent compliance record especially in cases where the Court ordered monetary compensation. In Ibrahim Mainassara v Niger,36 representatives of the former president approached the ECCJ seeking full investigation of the incident in which a group of armed men attacked and killed the then president at the Niamey Military Airport on 09 April 1999. The Court found violations of the right to access to justice and the right to life. It further ordered Niger to pay 435 000 000 FCFA to the family of the deceased former president. Niger fully paid these amounts by 2018. The state of Niger also fully complied in the case of Dame Hadijatou Mani Koraou v Niger37when the Court awarded the Applicant 10 000 000 FCFA as compensation for placement in servitude.

An applied political economy analysis of Niger seems to reveal that the country’s political will seems to be propped by its desire to be viewed as a budding democracy especially in the wake of a military coup over a decade ago. It also shows that remedies involving payment of monetary compensation are more likely to be complied with as opposed those requiring law reform or release of prisoners.

Third, there is no available data on the status of implementation on the majority of the decisions of the Court. There are many implications of this state of affairs. One of them is that the Court does not have a database of such data, meaning that it might know very little about the fate of its decisions in the Community. Further, lack of data goes to show that assessing the status of implementation is a complex process that requires several stakeholders other than the parties to the decision, to provide real time information on the ground. Lack of critical data should be a call for more commitment to empirical research on implementation to establish attitudes, perceptions and understanding of national authorities regarding factors they consider in deciding whether to implement a court decision or not.

Fourth, decisions constituting ‘partial implementation’ reflect a trend where states seem to find it easier or expedient to comply with the monetary component of the court orders. This is also the case with cases of full compliance especially where the Court only awarded damages and costs of suit.38 However, such states would struggle with reform-oriented orders with more political implications. For instance, in Chief Ebrima Manneh v The Gambia, the Applicant was never released from detention but monetary compensation was paid.39 In Deyda Hydara Jr v The Gambia,40 the ECCJ ordered for full investigation into the murder and payment of damages. The state has not yet conducted the investigation but has already paid the monetary component of the judgment. The next section attempts to deduce factors that have a bearing on implementation of decisions of the ECCJ in particular, but also in general given that the same states are members of other human rights systems.

3 1 Factors affecting implementation of decisions

Some of the reasons behind this compliance trend include, first, lack of evidence of political will in implementation. The question of political will is easier alleged than proven. It is necessary that sentiments about political will be supported by political economy analysis of each country and engagement with designated national authorities responsible for implementing decisions. Such interaction will result in better understanding of the political dynamics concerned in specific decisions at a given time in each respondent state.

Second, there is lack of a framework for collaboration between the Court and other actors such as civil society organisations in terms of monitoring and reporting on implementation.41 This paper already argued that a process that is not monitored cannot be accurately assessed in terms of aspects that work and those in need of review. The greatest weakness of the ECOWAS human rights architecture now is the absence of a systematic monitoring framework by an organ that seeks to hold states accountable for their non-compliant behaviour. The adoption of instruments to further hold states accountable to their obligations under Community law is needed. Key to the monitoring mechanism is designation of national authorities responsible for receiving writs from the ECCJ. The new ECJ approach to require respondent states to report on implementation is new impetus that could result in some overall improvement.

Third, the practice of the system so far does not seem to compel states to comply although the legislative framework provides that decisions of the ECCJ are final and binding, essentially. There is a need to find a way to formally involve ECOWAS policy organs to exert pressure on specific non-complying states through the deployment of the sanction’s regime, which to date has not been utilised for this purpose.

Fourth, national institutions such as courts have not embraced their role in executing judgments of the ECCJ in accordance with the civil procedure of each state as the new article 24 of the 1991 Court Protocol contemplates. In this regard, In the Matter of an Application to Enforce the Judgment of the Community Court of Justice of the ECOWAS against the Republic of Ghana and In the Matter of Chude Mba v The Republic of Ghana,42 the High Court of Ghana declined to recognise the ECCJ decision in Mba v The Republic of Ghana.43 In other cases, the same Court declined an order for provisional measures arguing in the process that there is no need for them to ‘share jurisdiction with any other Court’.44 It appears that some national courts are engaged in the fight for jurisdictions as opposed to judicial co-operation. There is need for the ECOWAS to accelerate efforts to interface with heads of national courts and diffuse these territorial tensions, as national courts are key players in enhancing implementation by accepting and enforcing ECCJ writs in terms of article 24(2) of the amended 1991 Court Protocol.

Fifth, clarity of remedial orders of a court plays a major role in terms of implementation of a decision.45 As indicated above, implementation is a process of adopting measures to achieve the compliance outcome. Therefore, it is necessary for a court to be clear to give national authorities an opportunity to adopt appropriate measures in execution. Evidently, the ECCJ is a trailblazer in terms of issuing orders with clarity. Its monetary orders are specific without need for subsequent calculations and the Court is clear on non-monetary remedies such as orders for the release of detained persons,46 environmental rehabilitation,47 full investigation into commission of crimes48 and so on.

Sixth, there is need for a sanction’s regime, even if it only exists as a threat to recalcitrant states. This paper argues that, further to the debate on theories of compliance and their bearing on implementation, it appears the ‘coercion-centric approaches’ hold firm within the ECOWAS Community law. Article 77 of the Revised Treaty reaffirms coercion for non-compliance with Community obligations as follows:

- Where a Member State fails to fulfil its obligations to the Community, the Authority may decide to impose sanctions on that Member State.

- These sanctions may include:

- Suspension of new Community loans or assistance;

- Suspension of disbursement on on-going Community projects or assistance programmes;

- Exclusion from presenting candidates for statutory and professional posts;

- Suspension of voting rights; and

- Suspension from participating in the activities of the Community.

- Notwithstanding the provisions of paragraph 1 of this Article, the Authority may suspend the application of the provisions of the said Article if it is satisfied on the basis of a well-supported and detailed report prepared by an independent body and submitted through the Executive Secretary, that the non-fulfilment of its obligations is due to causes and circumstances beyond the control of the said Member State.

- The Authority shall decide on the modalities for the application of this Article.

This paper argues here that this enforcement framework or sanction’s regime applies with full force to non-compliance with ECCJ decisions. The duty to comply with court decisions is based on ECOWAS legal instruments that impose obligations on respective states. The paper further argues that non-compliance with decisions made by an ECOWAS organ falls squarely within the parameters of article 77(1) above. The sanction’s regime appears comprehensive and if utilised could result in improved compliance with obligations. However, to date there is no evidence of it ever having been deployed to induce execution of decisions of the ECCJ in spite of a growing non-implementation crisis in the bloc. Admitted, such measures are rarely used in practice.49

3 2 Duty of ECOWAS states to comply

As highlighted above, the 2005 Supplementary Protocol brought about sweeping changes with far-reaching consequences on the operations of the ECCJ as well as further obligations on states. Even prior to this, article 15(4) of the Revised Treaty of ECOWAS already provided that judgments of the Court shall be “binding” on member states, the institutions of the community and on individuals and corporate bodies. In addition, Article 22(3) of the 1991 Court Protocol provides that member states and institutions of the community shall “immediately [take] all necessary measures to ensure execution of the decision of the Court”, and by virtue of the customary international law rule of pacta sunt servanda,50 ECOWAS member states are obliged to abide by and comply with all decisions of the Court.

Through the 2005 Supplementary Protocol, ECOWAS member states specifically committed themselves to the full implementation of Court decisions. The new Article 24, which was absent from the original 1991 Court Protocol is dedicated to articulating methods of implementation of the Court’s judgments. Pursuant to the provisions of Article 24, “judgments of the Court that have financial implications for nationals of member States or Member States are binding”. It is my submission that even though this provision refers expressly to judgments that have financial implications, all judgments of the Court are binding, whether or not they have financial implications, pursuant to Article 15(4) of the Revised Treaty referred to above. More so because all court decisions are a consequence of a state’s failure to fulfil its legal obligations arising from binding provisions of community law instruments. Therefore, to the extent that treaty provisions are binding, so too are decisions rendered in the course of their enforcement. As will be revealed in the analysis of cases to follow, it would be illogical to have a court decision requiring the state to launch an investigation into unlawful death as non-binding while the monetary part of it is binding.

The new Article 24 also provides that the execution of any decision of the Court shall be in the form of a “writ of execution”, which shall be submitted by the Registrar of the Court to “the relevant Member State for execution according to the Rules of civil procedure of that Member State”.51 Upon verification by the appointed authority of the recipient member state that the writ is from, the “writ shall be enforced”. In terms of Article 24(5), the writ of execution may only be suspended by a decision of the ECOWAS Court.

A key provision pertaining to execution of Court orders is Article 24(4). Its essence is that Member States are to “determine the competent national authority for the purpose of recipient (sic), processing of execution, and notify the Court accordingly”. At present only six? states have nominated a national authority. These are Mali, Guinea, Nigeria, Burkina Faso, Togo52 and Ghana.53 However, even though these states have nominated an agency, no procedure has been formally provided for litigants to follow up with a national authority to ensure compliance with the Court’s judgments. However, it is noteworthy that some states that are yet to appoint authorities for implementation of the Court’s judgments, have been complying with the judgments in which they are parties. A good example of this is the Republic of Niger, which has complied with at least three cases out of four covered in this paper. 54

3 3 Monitoring implementation of ECCJ decisions

Monitoring implementation of court decisions is a huge part of the compliance matrix. It enhances performance in this area. Monitoring takes place when a mechanism is installed for taking stock whether or not states are, in each case, taking measures to implement decisions of the Court. It is through monitoring that a verdict of no, full or partial compliance can be made in respect of each decision. In instances where the Court has listed remedial measures, tracking the monitoring process takes an audit as to whether any, some or all of the listed measures have been adopted. Where the architecture establishes an organ to monitor implementation, as is the case with the CoM in the CoE,55 or the monitoring of compliance with decisions of the African Court on Human and Peoples’ Rights (African Court),56 this could be classified as political monitoring or supervision.

In other instances, however, the court that rendered the decision takes interest in the implementation and conducts monitoring of its decisions especially in instances where the political or policy organ is ineffective in its work. This manner of monitoring is termed judicial monitoring of compliance or implementation. Quite often, judicial monitoring manifests when the court, in the orders section of the judgment, requires the state to report to it within a stated period on the measures the state respondent has taken to implement the judgment.

Judicial monitoring was largely unknown in the ECCJ until the 2020 decision in Cheick Gueye v Republic of Senegal.57 The proceedings arose when the Applicant alleged that Senegal violated his right to property when it auctioned his property without any prior notice or compensation, contrary to Article 14 of the African Charter and Article 17 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR). The Applicant also alleged violation of the right to a fair hearing when the Respondent State failed to serve him with a hearing notice regarding the auction proceedings. The Applicant prayed to the Court to find the Respondent liable for these violations and award compensation. The Court obliged and found that Senegal had violated the Applicant’s right to property and fair hearing and ordered Senegal to pay 85 000 000 FCA.58 As a first in its practice, the Court went further to order Senegal to “submit to the Court within six months from the date of notification of this judgment, a report on the measure[s] taken to implement the orders set forth herein”.59 Other courts such as the African Court have adopted this approach for some time. It remains to be seen what measures the ECCJ would take in the event that Senegal neither complies with the decision nor files a report on the measures it has taken.

Concerning political supervision of implementation, the ECOWAS bloc again stands out as a model for inter-governmental organisations in adopting instruments seeking compliance with Court decisions. It has in essence made compliance a collective responsibility. In this regard, ECOWAS member states adopted the Supplementary Act on the Imposition of Sanctions against Member States that do not honour their obligations towards ECOWAS to deal with the issue of non-compliance.60 It should be recalled, however, that the Supplementary Act is not confined in its application to non-compliance with ECCJ decisions. The Act covers non-compliance with decisions of other ECOWAS institutions as well, and this paper submits here that ECCJ decisions are ECOWAS decisions because the Court is an organ of the ECOWAS.

4 Conclusion

The survey has demonstrated that the ECCJ is coming of age in spite of the teething problems it had over the human rights mandate. This experience was not unique to it as the other sub-regional tribunals also fought for competence. This was later clarified and settled by the ECOWAS policy organs. The study revealed that largely, the status of implementation of its decisions is far from desirable and much needs to be done to improve on this aspect. There exists a progressive legal framework to support efforts seeking better implementation of its decisions. The Court has also joined in monitoring implementation by requiring respondent states to report to it on measures adopted to implement each decision.

The study further revealed a number of good practices that can be emulated in other regions. These include: first, a robust sanction’s regime, without which implementation of decisions has little chance of success. However, where incentives have had little effect in terms of influencing change, policy organs may resort to sanctions lest the common values and objectives of the inter-governmental organisation are defeated.

Second, the practice of designating national focal points for purposes of receipt of writs from international courts/tribunals/bodies is emulated. The most important aspect of this practice is that such designation is required by statute as opposed to just being a best practice. Codification of this requirement is an expression of the ECOWAS conviction that it is an essential part of the design of the system for enhanced communication between the ECOWAS and national authorities. Such communication is a clear catalyst of successful execution of decisions of the Court.

Third, use of domestic procedure for enforcement of international decisions is important. This goes a long way in clarifying the status of decisions of international courts, tribunals, or quasi-judicial bodies in domestic law. In this regard, national courts and authorities would be required to recognise the ECCJ decisions for purposes of enforcement, thereby increasing chances of implementation of such decisions at national level.

Fourth, establishment of national offices in RECs may be an impetus to implementation. Whether these are combined with national focal points or are standalone institutions would aid the implementation of decisions by virtue of having a national presence.

Fifth, the clarity of the remedial measures of the Court will assist in improving implementation, because so far respondent states have not seen any need to utilise the “interpretation of judgment” provisions in the Rules of Procedure for the Court.

4. The Pan-African Lawyers Union (PALU) conducted the Baseline Report on the State of Implementation of the Economic Community Court of Justice in 2019, under the auspices of the RWI African Regional Programme. This article summarises the findings of the evidence-based Baseline Report to facilitate dissemination of these findings to reach a wider audience in Africa and beyond.

6. The ECCJ initially had seven full-time judges, appointed by the ECOWAS Authority of Heads of State. Since 2018, this number has now been reduced to five following a restructuring of ECOWAS institutions. The judges serve a five-year tenure and are eligible for reappointment only once. The judges select the President and Vice-President of the Court from amongst themselves. The President and Vice-President serve in this capacity for three years.

8. Supplementary Protocol A/SP.1/01/05, amending the Preamble and Arts 1, 2, 9, 22 and 30 of Protocol A/P.1/7/91 Relating to the Community Court of Justice and Art 4 Para 1 of the English Version of the said Protocol.

11. Adjolohoun Giving Effect of the Human Rights Jurisprudence of the Court of Justice of the Economic Community of West Africa States: Compliance and Influence (LLD dissertation 2013 UP) 55.

12. CCJ Official website ‘ECOWAS Court sets a new record in 2018 with the number of cases’ http://www.courtecowas.org/site2012/index.php?option =com_content&view=article&id=464:ecowas-court- sets-a-new-record-in-2018-with-the-number-of-cases- (last accessed: 2019-01-05).

13. See the introductory parts on the acceptance of the human rights mandate by RECs throughout the continent.

14. Ebobrah “Critical Issues in the Human Rights Mandate of the ECOWAS Court of Justice” 2010 Journal of African Law 1 at 2. See further Alter, Helfer and McAllister “A New International Human Rights Court for West Africa: The ECOWAS Community Court of Justice” 2013 The American Journal of International Law 737.

19. See Arts 6(d) and 7(2) of the East Africa Community Treaty and Art 16 of the SADC Treaty. For cases see James Katabazi v Secretary General of the EAC (Ref 1 of 2007) EACJ First Instance Division (31 October 2007)for the East African experience; and Mike Campbell v Zimbabwe SADC (T) Case 2/2007 for judicial activism in favour of human rights related jurisdiction in the SADC.

21. Ebobrah “A Rights-Protection Goldmine or Awaiting Volcanic Eruption: Competence of, and Access to, the Human Rights Jurisdiction of the ECOWAS Community Court of Justice” 2007 AHRLJ 307 at 312-321.

22. Raustiala “Compliance and Effectiveness in International Regulatory Co-Operation” 2000 Case Western Reserve Journal of International Law 387 at 391. See also Kingsbury “The Concept of Compliance as a Function of Competing Conceptions of International Law” (1997-98) Michigan Journal of International Law 345 at 346. However, this author, though acknowledging this definition, proposes that compliance should be examined not as a concept capable of standing alone, but in the context of existing theories of law related to it.

23. Haas “Compliance with EU Directives: Insight from International Relations and Comparative Politics’ 1998 Journal of European Public Policy 17 at 18.

31. Individual measures are those measures adopted by a state in executing a judgment that address the personal circumstances of the applicant, for instance, payment of compensation. On their part, general measures are those steps taken by the state to deal with guarantee non-recurrence of violation such as removing the law, which triggered the violation of right the case concerned.

32. The Council of Europe is an inter-governmental organisation made up of European states and headquartered in Strasbourg, France. All Council of Europe member states have signed up to the European Convention on Human Rights, a treaty designed to protect human rights, democracy, and the rule of law. The Committee of Ministers is the Council of Europe’s statutory decision-making body. Its role and functions are broadly defined in Chapter IV of the Statute. It is made up of the Ministers for Foreign Affairs of member states. The Committee meets at ministerial level once a year and at Deputies' level (Permanent Representatives to the Council of Europe) weekly. In accordance with Article 46 of the Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms as amended by Protocol 11, the CoM supervises the execution of judgments of the European Court of Human Rights. This work is carried out mainly at four regular meetings (DH meetings) every year. See further Council of Europe website https://www.coe.int/en/ (last accessed: 2021-09-10).

33. Rule 6(2) of the Rules of the Committee of Ministers for the Supervision of the Execution of Judgments and of the Terms of Friendly Settlements (adopted by the Committee of Ministers on 10 May 2006 at the 964th meeting of the Ministers’ Deputies and amended on 18 January 2017 at the 1275th meeting of the Ministers' Deputies). Available at https://rm.coe.int/16806eebf0 (last accessed: 2021-09-10) .

34. The ECOWAS Court of Justice has delivered 261 judgments on 496 cases filed before the Court since its inception in 2003, according to the 2020 judicial statistics released by the Registry of the Court, Available at: CCJ Official Website “ECOWAS Court Issues 2020 Judicial Statistics” http://prod.courtecowas.org/2021/01/21/ecowas-court-issues-2020-judicial-statistics/ (last accessed: 2021-02-23).

38. Registered Trustees of Socio-Economic & Accountability Project (SERAP) v Federal Republic of Nigeria Application ECW/ECCJ/APP/10/10; Modupe Dorcas Afolalu v Nigeria Application ECW/ECCJ/APP/04/12; Ameganvi Isabelle Manavi v Togo Application ECW/ECCJ/APP/12/10.

39. ECW/ECCJ/APP/04/07. The facts were that two plainclothes officers of the National Intelligence Agency arrested Manneh at the office of his newspaper, the pro-government Daily Observer, according to witnesses. The reason for the arrest was unclear, although some colleagues believe it was linked to his attempt to republish a BBC article critical of President Yahya Jammeh. He was never seen again amidst government making public statements denying knowledge of his whereabouts.

41. On the impact of visibility of decisions on their implementation, see Murray “Confidentiality and the Implementation of the Decisions of the African Commission on Human and Peoples' Rights” 2019 AHRLJ 1.

44. Ruling of the African Court on Human Rights Rejected by Ghana’s Supreme Court” The Sierra Leone Telegraph (2017-11-30) http://www.thesierraleone telegraph.com/ruling-of-the-african-court-of-human-rights-rejected- by-gha nas-supreme-court/ (last accessed: 2021-09-10). However, the President of Ghana’s designation of the AG as the national focal authority for ECCJ decisions could thaw national courts’ attitude towards the regional Court. Designation implies co-operation with the Court.

45. Murray and Mottershaw “Mechanisms for the Implementation of Decisions of the African Commission on Human and Peoples' Rights” 2014 Human Rights Quarterly 349; Murray, Long, Ayeni andSomé “Monitoring implementation of the decisions and judgments of the African Commission and Court on Human and Peoples' Rights” 2017 AHRY 150.

47. Registered Trustees of Socio-Economic & Accountability Project (SERAP) v Nigeria Suit ECW/ECCJ/APP/08/09.

49. There is no record of the AU utilising Art 23 of the Constitutive Act of the African Union or the CoM utilising Art 8 of its Statute to induce compliance with decisions of the African Court and European Court on Human Rights, respectively.

50. This is an established international law principle that provides that states should implement their international obligations in good faith.

52. For a full list of countries that have appointed national points, see: CCJ Official Website “Court Receives Instrument Designating Ghana’s Attorney General as National Authority for the Enforcement of its Decisions” http://www.courtecowas.org/2020/07/08/court-receives-instrument-designating-ghanas-attorney-general-as-national-authority-for-the-enforcement-of-its-decisions/ (last accessed: 2021-09-10) (accessed on 20 June 2021).

53 Ghana is the latest country to advise the ECCJ on 21 October 2019 that the Attorney-General is the national focal point. The President of the ECCJ

53. remarked, “By this action, the President (President of Ghana) has contributed significantly to strengthening the Court in the discharge of its mandate as well as the promotion of the rule of law and protection of human rights, which has become its defining mandate”.

54. Mamadou Tandja v General Salou Djibo ECW/ECCJ/APP/05/09; Ibrahim Mainassara v Niger ECW/ECCJ/APP/25/13; and Dame Hadijatou Mani Koraou v Niger ECW/ECCJ/APP/04/07.

56. Art 29(2) of the Protocol to the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights on the Establishment of an African Court on Human and Peoples’ Rights (African Court Protocol) provides that the Executive Council of the AU shall be notified of any final African Court decision for purposes of monitoring execution on behalf of the AU Assembly of Heads of State and Government.