Evelyne Asaala

PhD (Wits) LLM(Pretoria) LLB (Nairobi)

Lecturer, School of Law, University of Nairobi

Volume 54 2021 pp 430-452

Download Article in PDF

SUMMARY

Fifteen years after inception offers the best time to assess the mechanisms and framework of implementing decisions of the African Court. Yet, within this time, of the ten member states that have made a declaration under article 34(6) of the Protocol to the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights on the Establishment of the African Court (The African Court Protocol), four have withdrawn their declaration amidst a general decline of states’ trust in the Court. This has adverse implications on the implementation of the Court’s decisions and the creation of a general culture of human rights on the continent. This is particularly so in light of the fact that the origin of majority of applications before the Court originate from individuals enabled under this declaration. The involvement of the AU policy organs (the Assembly and the Executive Council) and member states has the potential to further compound the challenges facing the question of implementation of the Court’s decisions. This chapter offers a critique of the effectiveness or otherwise of the implementation process of the African Court decisions as well as the challenges impeding effective implementation.

1 Introduction

The implementation of decisions pronounced by regional human rights tribunals is a subject of global concern and stands at the centre of the infrastructure of modern international human rights systems. It is only with effective implementation systems that regional human rights institutions become meaningful and human rights values can materialise. It is thus unsurprising that the African Union (AU) has established the African Court on Human and Peoples’ Rights (the African Court) to ensure respect and compliance with the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights and other human rights instruments of the AU; the European Union has established the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) to guarantee the enforcement of the European Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms and other European human rights instruments, and the Organisation of American States (OAS) has established the Inter-American Court of Human Rights (IACHR) to ensure compliance with the American Convention on Human Rights and other human rights instruments of the Inter-American system. The concern on effective implementation of decisions made by regional tribunals certainly arises in relation to the African Court. Reports indicate a full compliance rate of seven per cent, excluding partial compliance.1 Moreover, of the ten member states that have made a declaration under article 34(6) of the Protocol to the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights on the Establishment of the African Court (The African Court Protocol),2 four have withdrawn their declaration3 amidst a general decline of states’ trust in the Court.4 These reactions by states are likely to occasion adverse implications on the implementation of the Court’s decisions.

While the African Court can be said to have a mandate to ensure implementation of its decisions, a mandate which is inherent in judicial organs, other entities also have a role to play in ensuring effective implementation.5 Indeed, the African Court Protocol envisages a primary role for state parties.6 The Protocol further attests to the significant position of the AU Assembly which has an obvious role to play in the implementation process.7 In executing its mandate, the Protocol calls on the Court to “submit to each regular session of the Assembly, a report on its work during the previous year [and to] specify, in particular, the cases in which a State has not complied with the Court's judgment”.8 Moreover, the Executive Council of the AU “shall also be notified of the judgment and shall monitor its execution on behalf of the Assembly”.9 The involvement of several players, for example, the AU Assembly, the Executive Council and member states in addition to the role of the Court has the potential to pose challenges to the implementation of the Court’s decision at both the respective institutional levels as well as the horizontal and vertical levels of the African human rights systems. This is because, at the horizontal level, the African Court must maintain a strategic partnership with the AU Assembly and the Executive Council of the AU in order to guarantee a coordinated approach in the implementation process. Similarly, at the vertical level, the African Court has an obligation to develop a working relationship with states parties mandated to comply with and execute its decisions. Yet, at the institutional level each of these institutions face context specific challenges relating to their respective roles in the implementation of the Court’s decisions.

The question on implementation of the decisions of the African Court thus arises both as a doctrinal matter and also as a matter of practice. The paper therefore considers the practice and doctrine relating to the implementation of the Court’s decisions with a focus on the role played by the Court, member states, the AU Assembly and the Executive Council. In particular, it assesses the legal, institutional and procedural effectiveness in the implementation process with the aim of strengthening the current system. The challenges that hinder effective implementation of these decisions at both institutional level as well as the horizontal and vertical institutional relations will be a key component of this paper. In this regard, a report developed by the ACC in conjunction with the RWI serves as a point of reference in contextualising this study. Accordingly, other than the proceedings of a consultative forum on the African Court held in 2019,10 the paper is largely based on desk research and interviews of legal experts who have worked or are currently working with the Court. The discussion draws insights, lessons and best practices from the Inter-American Court and the European Court and also general literature on the subject matter.11

Against this background, the objective of this article is to assess the implementation framework of the African Court’s decisions, identify the challenges that impede effective implementation and discover opportunities for enhancing cooperation among the entities involved. The article is divided into four parts. These include, the introduction, the normative framework of implementing the Court’s decisions, an in-depth analysis of the mechanisms involved in the implementation process, their powers, the tools they deploy and their established practice in implementing the Courts’ decisions for the last fifteen years. The discussion on the practice also captures the relationship of the respective mechanisms with the Court. This discussion should ably bring out the challenges in the process of implementation as well as point out the opportunities for effective cooperation between these entities. Finally, the paper offers some concluding remarks.

2 The normative framework for implementing the African Court decisions

One of the main objectives of the AU is to “ promote and protect human and peoples’ rights in accordance with the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights and other relevant human rights instruments”.12 The reference, to “other relevant human rights instruments” implies the consideration of other AU and UN human rights instruments.13 For example, the Maputo Protocol, the African Children’s Charter, the UN Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW) and the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child.

In its Preamble, the African Court Protocol expressed the AU’s firm belief that “the attainment of the objectives of the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights requires the establishment of an African Court on Human and Peoples’ rights”.14 The African Court is one of the main organs of the AU responsible for enforcing the Charter and other human rights instruments and must also guarantee implementation of its decisions. To achieve these objectives, the Court exercises its diverse mandate of adjudication, advisory opinions and conciliation of disputes.15

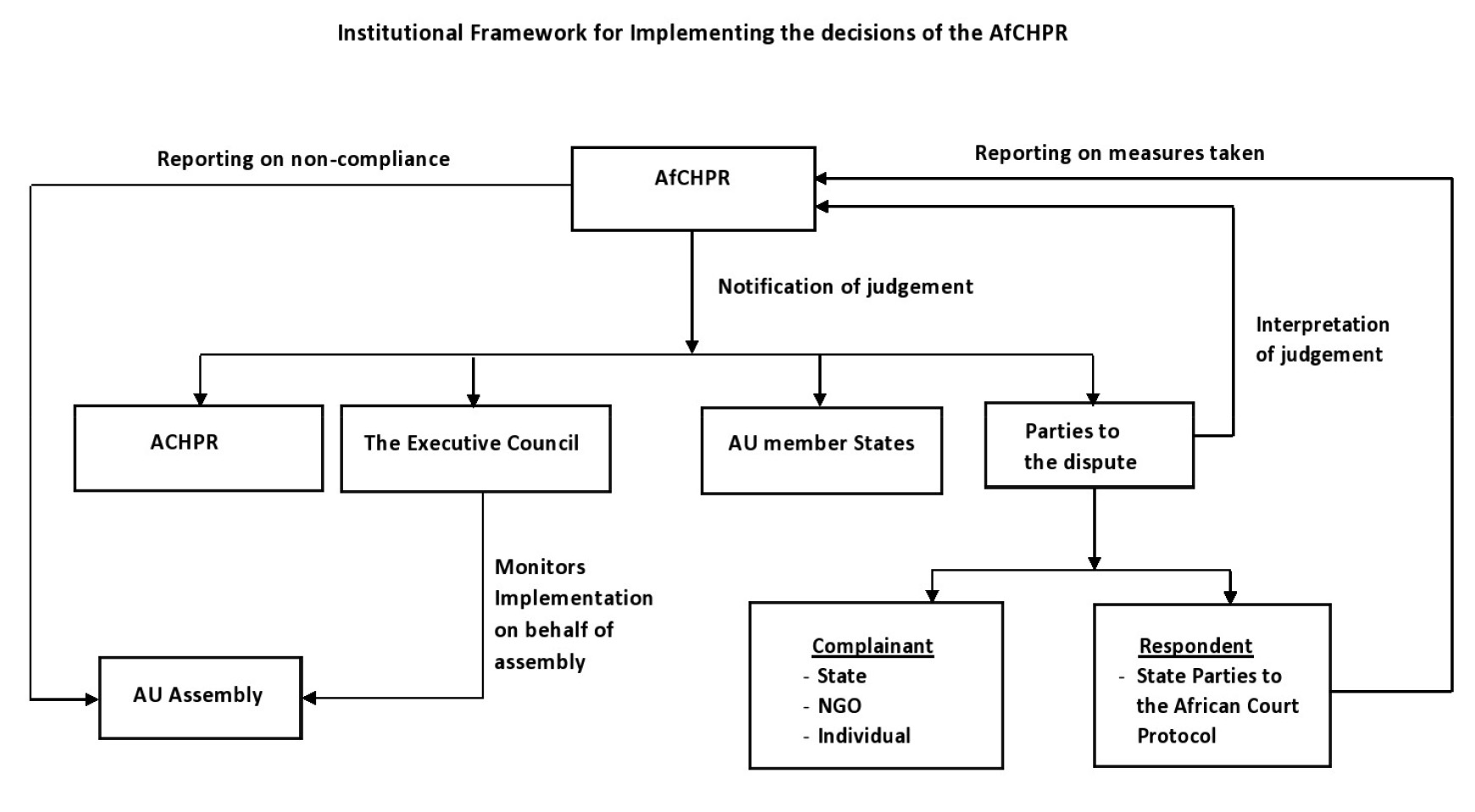

Despite its broad mandate, this article will focus on the Court’s adjudication mandate since this mandate approves judicial pronouncements that are binding in nature on the respective parties to a case. Article 27 of the Court’s Protocol embodies the remedial competence of the Court in both standard proceedings and urgent matters.16 Article 29 further mandates the Court, after making a decision, to notify the parties to the case and to have the judgment transmitted to all member states of the AU, the African Commission and the Council of Ministers.17 In the case of interim measures adopted by the Court, the Court has the mandate to invite the state party concerned to provide information on the measures it has adopted towards implementing the interim measures.18 Non-compliance with the Court’s decision and its interim measures, obligates the Court to report such conduct to the Assembly.19 However, a state party seeking clarification on what is expected in terms of implementing the judgment can seek such clarification according to Rule 66 of the Court’s Rules of Procedure. The normative framework of implementing the decisions of the Court is succinctly explained in the diagram below.

The African Court Protocol is clear on the procedure and role of the various AU organs involved in the implementation process. Yet, a full account of the implementation process is only possible by an appraisal of the practice of the respective organs.20 This practice, in the context of this study is significant for two reasons. First, it helps to more fully circumscribe the powers, mandate and role of the organs in the implementation process. Second, it appreciates other secondary players

not expressly mentioned under the Court’s Protocol.21 The procedure as provided under the legal framework only mentions the primary players in the implementation process. As our discussion will later reveal, the implementation process is more complicated and involves several secondary players whose role is equally instrumental in the implementation process of the Court’s decisions.

3 The mechanisms, their practice and opportunity for strategic partnership in the implementation process

Having established the normative framework and the general procedure of implementation in the previous section, the current section discusses the powers, tools and the practice of the various mechanisms, the challenges as well as opportunities for an effective cooperation framework in the implementation process. While general statistics on the Court’s decisions may be readily available, the procedural and substantive aspects of what follows in the implementation process and the role of the respective organs of the AU and its member states are not well established, understood and documented. The following sections do this by discussing the powers of the Court as an institution and also in relation to AU policy organs, the tools available to these institutions, and their practice in implementing the Court’s decisions. It will also allude to institutional challenges facing the Court and the other entities involved in the implementation process. Given the significance of having an effective implementation framework for the decisions of the Court, it is important to consider the day-to-day workings in these institutions and how they impact on the overall question of implementation.

3 1 The role of the African Court in implementing its decisions

The African Court bears one of the key responsibilities in implementing its decision. Thus, to give effect to the principles of the African Human Rights system, one must discuss the institutional mechanisms designed by the Court in this regard and their practice. Yet, different ideologies within the Court as to the role it should play in the implementation process define the Court’s approach on this matter.22 It should be noted that the African Court is comprised of judges from several legal backgrounds and traditions.23 The different and sometimes divergent views of judges from different legal philosophies is what this contribution perceives to be a potential reason that may explain the current lack of clarity in either the practice of the Court or in the development of the law on the role of the Court in implementing its decisions. On one end of the spectrum, some judges contend that the Court should play a passive role in the implementation and monitoring process leaving these functions to states and policy organs of the African Union.24 On the other end some judges argue the Court should play a more active role in implementation of decisions.25 It can be argued that the lack of coherence in the ideological approaches to the Court’s role in the implementation process is what has compromised a coordinated advancement of the Court’s practice in implementing its decisions. This has also been compounded by the absence of specificity in the Court’s Protocol.

Nonetheless, like its counterparts in the European system and the Inter-American system, the African Court has a post-judgment role regarding the implementation of its decisions. Firstly, the Court has the mandate to interpret its own decisions.26 While in the European system it is the body supervising the implementation process, the Committee of Ministers (CoM), that seeks an interpretation of a judgment, in the African Court system it is the parties to the dispute that are authorised to seek its interpretation.27 Essentially, this interpretation is important for the parties to the dispute as it enables them to understand with clarity the measures to be undertaken in the implementation of the judgment. The interpretation is also equally important to bodies responsible for supervising the implementation process, like the CoM in the European system, as it enables them to assess the measures to be taken or being taken by a contracting state in the execution of the judgment. However, although the parties to the dispute before the African Court can seek this post-judgment interpretation, the follow-up mechanisms after this kind of interpretation have not been provided for under the law. This implies that it is not clear on what exactly should be done and who bears the responsibility. What seems clear is that the Court sits back and waits for the state party’s report on its compliance. The Court has not devised any internal mechanisms like follow-up site visits to assist the involved states in the implementation process of its own interpretations, particularly in areas that the state may be facing challenges.

Also, the African Court monitors its decisions through its own judgments and rulings. In practice, the Court calls upon member states to report back to it within a specified period of time specifying the measures it has taken to implement the judgment. The Court normally indicates in its judgment the time period within which a member state should report back on the measures it has taken. The clause “the Respondent ... to inform the Court of the measures taken within six (6) months from the date of this Judgment” initially appeared in all its judgments.28 This, evidences the fact that after rendering its judgment, the Court waits for the relevant member state to report back on the measures it has taken in implementing the decision. In order to address the challenge of states getting stranded on what to do in the event they fail to report within the six months, the Court has recently adopted the practice of requiring its member states to report back every six months until full compliance is attained.29 This practice enables the African Court to follow-up on the implementation process. The states that report back are then captured in the Court’s Annual Activity Report as having either partially of fully complied depending on their report and those that do not report are cited as being non-compliant.

Since the African Court does not have a follow-up mechanism between the date of delivery of the judgment or ruling requiring the state to comply and the time when the state reports back to the Court, this is likely to pose challenges. The possible challenge with this kind of approach is the possibility that a member state could be cited for non-compliance, yet on the ground initiatives are underway towards the implementation of the Court’s decision. In the ACHPR v The Republic of Kenya case (also known as the Ogiek case) although Kenya was reported as being non-compliant simply because the government had not filed an implementation report with the Court, evidence was later adduced to the effect that Kenya had actually taken steps towards implementation of the Court’s decision.30

In addition, the reporting exercise is inherently weak. It entails the relevant state filing the report with the Courts’ registry, and the report is analysed by the Legal Division to establish progress and formulate recommendations. These recommendations are purely based on the technical report and there is no verification of information. It also seems as though there is no structured further follow-up by the Court or any additional compliance orders or additional compliance related hearings in relation to non-complying states. Although there is follow-up correspondence from the Court asking the member states to report on compliance, such correspondence is either seldom responded to by states or where the state responds, it is mostly not clear on what measures it has undertaken or in some cases the state continues to advance its arguments that contradict the Court’s decision.31 In order to address some of these challenges the Court recently adopted its new rules, incorporating the aspect of compliance hearings similar to those in the Inter-American system.32

The Inter-American system has a similar practice where the Court requires the member states to report back on measures it has adopted in complying with its decision within a specific period. After a state submits its report, the IACHR shares it with the Inter-American Commission and the victims and also summons the parties to closed hearings on compliance.33 The IACHR then issues its report on compliance outlining the actions for the state and requiring further reporting of the state within a specific time.34 The practice of the IACHR is to retain overall control of the implementation process until it determines that a state has fully complied. The IACHR has put in place mechanisms to enable it to achieve its monitoring duty through these compliance hearings. They include: availability of information which the Court sources from the state, the victims and their representatives and the Commission; other than the hearings and further orders, the IACHR also conducts visits to states found responsible; it also conducts monitoring through notes issued by the Court’s Secretariat; and it has a monitoring unit dedicated exclusively to supervising compliance with judgments.35 Although judicial dominance in the implementation process as it is the case in the Inter-American system is beneficial in the sense that it maintains a rule-based approach by ensuring precision of rules and procedures in the implementation process it can also be detrimental to the extent that it lacks political ownership of the process.36 The IACHR has mitigated this negative impact by holding joint compliance monitoring processes of reparations ordered in judgments in several cases against the same states.

The Court employs this strategy when it has ordered the same or similar reparations in the judgments in several cases and when compliance with them faces common factors, challenges or obstacles.37

This has happened in both Dominican Republia and Colombia.38 Joint compliance monitoring can be an effective tool in the implementation process. Not only does it assist states with common parameters of identifying the obstacles to the process, it also guarantees some level of political buy-in thus gaining local legitimacy for the implementation process. It is important for policy organs to buy-in the process in order to give it political legitimacy. The African Court could thus borrow some of these good practices and also strive to establish a balance on the need for political legitimacy.

Like its counterparts from the IACHR and the ECHR, the African Court could also adopt the practice of action plans. Instead of waiting for a state to report back on the measures it has taken, the Court could, immediately after its judgment and before the reporting back period, require the state party to furnish it with an action plan detailing its proposed approach in the implementation process. This guideline is important for two reasons. First, it enables the Court to understand some context specific aspects that may be impacting on the state’s implementation process and second, it provides an opportunity for the rule-based Court to closely engage with the state in a process that provides the state with some room to determine the best way of implementing the Court’s judgment. As a result, guaranteeing some level of political will in the implementation process.

The African Court faces numerous institutional challenges that hinder its effective engagement in the implementation process. Key among them is the fact that the Court does not have dedicated staff who liaise with the Court or other AU policy organs and states parties on the implementation of its decisions. This means that the Court deals with the implementation question on an ad hoc basis making it difficult for it to closely follow-up on the implementation process. The need for the Court to appoint permanent staff to streamline record keeping and general coordination of the monitoring process of the Court’s decisions with other AU organs and states parties cannot be overemphasised. The fact that the Court has not prioritised establishing staff exclusively dedicated to the implementation of its decisions reinforces the finding from the interviews that the Court was mostly focused on addressing the problem of a backlog of cases as opposed to ensuring implementation of its decisions.39 One interviewee noted in this regard that the success of the Court should not be measured by the number of decisions it has delivered but the extent to which this has influenced a change of behaviour in a member state.40

Another set-back facing the Court concerns states’ withdrawal of their declaration under article 34(6). The four withdrawals in the last five years implies that if this trend continues then all the remaining member states to the African Court Protocol that have adopted the declaration are likely to withdraw in the next five years. The impact of the Court is also limited due to the number of states that are party to the Protocol. Of the 55 AU member states, only 30 have ratified the Protocol establishing the African Court. This means that the Court cannot influence national human rights values in the other 25 states. This is detrimental for the continent if the AU’s objective as captured under the African Charter is indeed to create a common continental approach in the promotion and protection of human rights. Given the significance of universal membership to the African Court as well as that of article 34(6) declarations in enforcing human rights standards on the continent, the need to lobby states to adopt this declaration cannot be underestimated. Nonetheless, unlike the policy organs of the AU, the Court is not in a position to conduct this lobbying.41

It is also very important that the Court, through practice and interpretation, defines its role in the implementation process with clarity. This will help in further developing its rules of practice in the implementation process as was the case with the Inter-American Court. The Court could also explore its fact-finding mandate to carry out site visits in an effort to assist member states comply with its judgments. This is a potential tool that can be utilised to create public discussions around the issue of implementation and also mount diplomatic pressure on the relevant state thus supporting the implementation process. In fact, the model used by the IACHR of joint monitoring of compliance would be most effective. Thus, before the African Court borrows some of the best practices from the IACHR and the ECHR, it is important that it first addresses its own internal challenges.

3 2 The relationship between the Court and the AU policy organs in the implementation process

The AU policy organs comprise the Assembly and the Executive Council. While the Assembly is composed of all the heads of state and government or their representatives from member states of the AU, the Executive Council is comprised of the Ministers of Foreign Affairs or any such Ministers designated by the government of member states to the AU.42 The role of the AU Assembly and that of the Executive Council in relation to implementing the Court’s decisions are intertwined. In practice, it is the Executive Council that carries out the functions of the Assembly.

There are two areas of interaction between the Court and the AU policy organs in the implementation of the Court’s decisions. First, the Assembly conducts the monitoring process through the Executive Council. The Executive Council of the AU “shall also be notified of the judgment and shall monitor its execution on behalf of the Assembly”.43 This implies that once the Court delivers a judgment and it is transmitted to the Executive Council, the Executive Council must commence the process of monitoring its implementation. In addition to monitoring the Court’s decisions, the Executive Council is bestowed with an extremely wide mandate “to coordinate and take decisions in areas of common interest to the Member States” which areas range from, amongst others, trade, energy, agriculture, environment, transport, insurance, education, communication, science and technology, nationality, social security and African awards.44 In all these areas, the Executive Council has the obligation not only to monitor the implementation “of the policies, decisions and agreements adopted by the Assembly” but also to “[r]eceive, consider and make recommendations on reports and recommendations from other organs of the Union that do not report directly to the Assembly”.45 The Executive Council meets at least twice a year, in which meetings, they are to deliberate on all these issues.46 Indeed, the interviews revealed that during such meetings, the Executive Council considers hundreds of reports concerning all the above issues.47 It is evident that such a process cannot allow the Executive Council to sufficiently deliberate on all the issues on its agenda including monitoring the Court’s decisions. In fact, it was noted that the Court is lucky if it gets an hour slot for discussion of its issues.48 The interviewee further revealed that, this hour is shared in discussing a host of other issues concerning the Court, for example its budget.49 The Court has also acknowledged that the Executive Council does not have the mechanisms to execute this mandate.50

Unlike the Executive Council of the AU, the CoM is the EU equivalent charged with the sole responsibility to supervise the execution of the ECHPR decisions. Functionally, the CoM is assisted by the Department for the Execution of Judgments of the ECHR.51 The CoM does not have any other additional responsibilities as its counterpart in the AU, the Executive Council. This guarantees some level of effectiveness in service delivery as opposed to a situation where a body is bogged down by numerous other responsibilities as is the case with the Executive Council of the AU. Out of 2705 decisions of the Court, 2641 have been fully complied with and the files closed.52 Moreover, while the Executive Council meets at least twice a year,53 in which meetings they are to deliberate on all the issues enumerated above, its counterpart, the CoM meets quarterly to deliberate on the execution of decisions of the ECHR.54 The narrowed mandate of the CoM allows sufficient time for detailed consideration of all the aspects concerning implementation of the Court’s decisions.

In addition to these AU policy organs are some secondary players not yet expressly mentioned under the Court’s Protocol, their involvement in the implementation process is key. They, for instance, include the Permanent Representative Committee (PRC) and the Specialised Technical Committees (STCs). The PRC is the technical organ of the AU that carries out the day-to-day work of the AU on behalf of the Assembly and the Executive Council.55 It is composed of one representative from each of the 55 member states and it prepares the work of the Executive Council and acts on its instructions.56 This includes “[m]onitor[ing] the implementation of policies, decisions and agreements adopted by the Executive Council”.57 The PRC has been able to achieve this through its sub-committees or working groups.58 In October 2019, the PRC sub-committee on Human Rights, Democracy and Governance was operationalised.59 It shall, as part of its mandate integrate the work of human rights bodies including the Court in the policy processes of the African Union.60

The Executive Council also works closely with the STCs, another organ of the AU which comprise ministers or senior officials in their respective areas of expertise.61 It is the STCs that have a direct responsibility to supervise, follow-up and evaluate the implementation of decisions taken by the organs of the AU.62 With respect to legal decisions by the Court, the STC on Justice and Legal Affairs63 has a direct role in supervising, following-up on and implementing its decisions. Save for the STCs on finance and monetary affairs; gender and women empowerment; defence and security, all the other committees are mandated to meet only once in two years.64 Although one meeting in a period of two years may not be sufficient for these STCs to effectively monitor the implementation process of all the legal decisions of the AU organs, including those of the African Court, the practise has some positive features. In reality, these meetings tend to last from one to three weeks thus providing sufficient time to deliberate on all issues under consideration. Since the STCs are composed of high-level technocrats from member states, they can offer more in-depth and technical discussions on matters under implementation. For example, if a country is ordered to amend its law, such a country may present a draft bill as evidence of implementation and the STC is better placed to examine whether the draft law meets the requirements contained in the Court’s decisions.

Considering that a state is likely to be cited for non-compliance for failing to report back to the Court in a year, it does not make sense for a body that is to assist in following up on the implementation process to meet only once in two years. Besides, there is no clarity on the mandate of the STC on Justice and Legal Affairs in so far as the implementation of the Court’s decisions is concerned. There is also no evidence to suggest that the STC has taken up this responsibility. Indeed, STCs remain to be a very vital organ in the implementation process.

Second, concerning non-compliant states, the Court is mandated to submit to the Assembly in “each regular session of the Assembly, a report on its work during the previous year [and to] specify, in particular, the cases in which a State has not complied with the Court's judgment”.65 The Court has duly executed its obligation on reporting to the Assembly through its annual Activity Reports. Yet, the AU has recently adopted a decision barring the Court from naming the non-compliant states.66 This undermines the spirit of article 31 of the Court’s Protocol and the African human rights system in its entirety.67

In addition to the Assembly, these activity reports are also communicated to the Executive Council, the PRC, and the Commission. Functionally, it is the Executive Council that considers them. In practice, and in light of the above scenario where the Executive Council considers numerous reports, there is insufficient time allocated to discussing non-compliance of the decisions of the Court in detail.68 Moreover, other member states have been reluctant to exert peer pressure on those states cited for non-compliance.69 Procedurally, a state party that has been cited for non-compliance may simply deny the allegations and or allude to national initiatives that it has undertaken in implementing the decision without sufficient verification from the other member states present. Civil Society has also been faulted for failing to advocate for necessary measures at national level and to lobby a critical mass of supportive member states to hold their peers accountable on such presentations.70 Thus ordinarily, there is limited accountability exerted from the floor. The absence of clarity in the relevant frameworks and the inherent weakness displayed by the institutions and actors involved in the process make the achievement of the objectives envisaged under the Court’s Protocol questionable. In fact, once the Activity Report has been presented to the Assembly there is no follow-up of those countries cited for non-compliance or those that have partially complied.71

It is also not clear whether the Court still has a role to require the cited states to report back to it on their further action or whether the Executive Council is mandated to follow up. What is clear is the fact that the Court continues to report non-compliance until the decision is fully implemented. In one of its previous decisions in response to the Court’s activity report, the Executive Council merely commended the states that had either partially or fully complied with the Courts order and urged those cited for non-compliance to comply.72 The aftermath of this kind of decision remains uncertain as it is not clear which institution is obligated to make a follow up of the eventual implementation. Since it is difficult to evidence practice in this aspect, it is not known whether such a follow-up should be done by either the Assembly or the Executive Council or PRC or STCs or it is for the relevant state to report back to the Court on the measures it has taken to comply with the decision of the Court.

Upon delivery of a judgment, the Court also has the responsibility to notify inter alia the African Commission.73 Again, the legal framework is not clear on the working relationship between the Court and the Commission with respect to implementation of the Court’s decisions or whether this relationship ends with the notifications. While it is clear that the Commission is one of the organs that can refer cases to the Court,74 it is not clear what role the Commission plays in assisting in the implementation of the Court’s decisions. Functionally, it is the Commission’s Office of the Secretary General that receives these judgments as well as the activity reports of the Court, which indicate the various levels of implementation and compliance with the Court’s decisions. Unlike the Assembly and the Executive Council, the Commission has a full-time secretariat. However, the Office of the Secretary General lacks full-time staff dedicated to the implementation of the Court’s decisions.75 The Commission serves a dual role of acting as a secretariat for both the Assembly and the Executive Council and also the bridge that links the Court to the AU policy organs. There is no direct day-to-day relationship between the Commission and the Assembly or the Executive Council in relation to the implementation process. To the extent that it acts as their secretariat, this is limited to transmitting documents from the Court to the policy organs and vice versa. In addition to the Department of Political Affairs, the rules of procedure of the Commission create meeting of the bureau of the Court and that of the Commission.76 These mechanisms can also be utilised in harmonising the roles of the two institutions in the implementation process. This may for instance include verification of member state reports. Like its counterpart in the Inter-American system, the African Commission can play an instrumental role in the implementation process. Upon receiving a compliance report from states parties, the Monitoring Unit of the Inter-American Court transmits such reports to the Inter-American Commission and also to the victims for them to react. This enables the Court to get the Commission’s as well the victims’ views on the recommendations and possible challenges in the implementation process.77 In fact, this contribution proposes the involvement of the Commission to begin much earlier at the stage where the Court considers a member states’ action plan. These action plans should be shared with the Commission and victims also in order to get their input on the implementation process.

Our discussion above has revealed that the relationship between the Court and AU policy organs in the implementation of the Court’s decisions is not effective. The specific roles played by both the primary and secondary organs involved are not at all clear and also the point at which one institutional mandate ends and that of the other begins is confusing. The fact that the legal frameworks provide for the involvement of numerous institutions which in practise do not have staff dedicated to the specific work of implementing the Court’s decisions is a major contributor to this confusion. The European system would offer a good comparative example in this regard. However, it should be noted that the statutes of both the AU and EU do not include similar provisions regarding implementation, compliance and monitoring of decisions. The EU has a clear system that entrusts one organ of the EU with the mandate to supervise implementation of the ECHR decisions. Once the ECHR makes a decision, the judgment is transmitted to the CoM to supervise its execution.78 After fulfilling the required procedures, the CoM has the mandate to seek interpretational questions of the judgment that may hinder its execution.79 It also has the mandate to refer the question of non-compliance to the Court where a contracting state refuses to abide by the judgment.80 If the Court finds a state in violation of its obligation to abide by the decision of the Court, it refers the case back to CoM to consider the measures to be taken.81 To the contrary, where the Court finds no violation of a state’s responsibility to abide by the judgment, it shall refer the case back to the CoM, which will be under a mandatory obligation to close its examination of the case.82

The CoM has devised its internal mechanisms which makes these achievable. Other than delegating most of its monitoring duties to its Secretariat,83 its rules of procedure require states to submit action plans on measures they have taken or intend to take in implementing the judgment.84 It should be noted that the secretariat has an entire department called the ‘Department on Execution of Decisions’ that assists the CoM in carrying out its supervision mandate. Moreover, the CoM has the power to access information on the progress made by states in executing the judgments.85 Such information can be sourced from the state concerned, aggrieved parties, NGOs, other national institutions or any other body involved in the proceedings.86 After collecting this information, the Secretariat prepares a status report in which it proposes to the CoM to either continue supervising the matter, or to partially close supervision on some items that are fully implemented or to close the case altogether if the Secretariat is convinced of full implementation.

The European system is, however, not above criticism. Although the CoM has delegated its role on monitoring to the Secretariat, there have been instances where state lobbying to have the CoM resolve to close some aspects of execution has defeated the advice of the Secretariat.87 Indeed, interviews revealed that central to the implementation of the African Court’s decisions is a political process that relies on the political will of the state party against whom the decision has been rendered and also the exertion of peer political pressure on the state.88 While a political body like the CoM is important in ensuring political buy-in of the implementation process, the African system must strive for a system that balances this against with the rule of law. A study conducted by the African Court acknowledges the exertion of pressure on a state by its peers as the most important aspect of the implementation process.89 The mixture of judicial and political approaches within the European system balances out the equation as the implementation process ceases to look like a judicial imposition as opposed to collective judicial, bureaucratic and political efforts. While the CoM has exerted the necessary peer pressure in implementing the ECHR decisions, some comparative efforts are lacking in the African Court system.90

In the absence of legal provisions on this aspect, this contribution calls for reforms that will see the Assembly of Heads of State and government complement the Executive Council in exerting peer pressure on noncompliant states in the implementation process. Like its counterpart in Europe, the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe, the AU Assembly can conduct follow-up country visits to closely monitor the implementation process and encourage its peer to complete the process.91 It can also call into action the sanctions regime. The central role of the AU Assembly in the implementation process must also be read in light of article 23 of the Constitutive Act which allows the AU Assembly of Heads of State and governments to impose relevant sanctions on “any Member State that fails to comply with the decisions and policies of the Union”. Such sanction measures range from denial of transport and communications links, as well as political and economic measures as may be determined by the Assembly.92 This provision sets out a very broad mandate, which without more, would suffice to establish the competence of the AU Assembly to enforce the sanctions regimes in matters concerning implementation of the Court’s decisions. Yet, the Assembly has to be very strategic whenever it decides to adopt these sanctions. This contribution suggests that before calling into action the sanction’s regime, the Assembly must first exhaust every constructive form of engagement with the affected states.

The need for a concerted approach in the implementation process of the Court’s decisions cannot be overemphasised. The fragmented and sometimes overlapping roles in the various primary and secondary organs of the AU must be streamlined to provide for a clear and linear process of implementation as discussed above. The current system begs for a clear framework with more clarity on the procedure and the duty bearers. Of priority is a framework that harmonises the role of all the institutions involved in the implementation process.

3 3 The relationship between the Court and member states in the implementation process

The African Court Protocol calls upon member states to recognise the rights, duties and freedoms enshrined in the Charter.93 In particular, member states have an undertaking to “comply with the judgment in any case to which they are parties within the time stipulated by the Court and to guarantee its execution”.94 The African Court Protocol further identifies additional measures that states are to adopt in fulfilling these purposes including adopting legislative or other measures to give effect to these rights, duties and freedoms.95 These comprise member state’s primary obligations.

In practice, the relationship between the Court and its state parties in the implementation process is too technical and often characterised by the challenges that hamper effective implementation. For example, other than the Court’s notification of the judgment and its receipt of compliance reports from the states, there seems to be no real time interaction between these two entities. With lack of site visits or joint activities in the implementation process, the relationship between the Court and its state parties can be summarised as a paper relationship. This denies the Court local political legitimacy which is essential for effective implementation of its decisions. Indeed, member states’ decisions to comply or not to comply is primarily a conscious political decision.96 Political will is therefore a central factor in the execution process and any efforts towards strengthening the implementation process and its mechanisms must first address the question of how to reinforce the demand for implementation of the Court’s decisions by states parties or essentially how to win over member state’s political will in the implementation process.

Notably, there are other factors that determine a member state’s conduct in the implementation process. For instance, there are aspects of financial and technical capacity, domestic political processes like elections, amongst others.97 More so, the lack of clarity on how domestic procedures can be adopted to enforce decisions of international bodies could also hinder a smooth implementation process. Depending on whether a member state ascribes to the philosophy of monism or that of dualism in the transformation of international law into domestic law, this has a direct impact on how the Court’s decisions are implemented at the national level. In the case of Alfred Agbesi Woyome v Ghana98 although Ghana, a dualist state, has ratified the African Court Protocol, it has not yet domesticated it. As such, the decision of the Court was not binding on Ghanaian Courts as required by the Constitution of Ghana. This calls for member states to align their domestic laws and procedure to their enforcement processes.

The lack of a national focal points to coordinate the implementation process at the national level and provide a constant link with the Court and AU policy organs is also a major hinderance to the implementation process. Currently, most of this coordination is fragmented among different government agencies and lacks coherence as all these agencies deal with a host of other issues. In some instances, countries have resorted to ad hoc mechanism in the implementation process. In the Ogiek case for example, Kenya appointed an ad hoc Task Force to look into the implementation of the Court’s decision.99 Granted that the implementation process at the national level involves different arms of government like the legislative arm and the judiciary; several ministries and or departments as well as the victims, the lack of an overall body charged with the responsibility to coordinate the various activities, supervise and follow-up on all these entities is likely to be counterproductive to the very objective of implementation. The Executive Council has previously urged AU member states to appoint focal points for the African Court from the relevant ministries.100 This borrows from the practice in the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS)101 where member states have established national focal points for purposes of receiving and overseeing the implementation process at the national level. Thus, for ECOWAS countries that also have such measures in place, their mandate could be expanded to include oversight over AU decisions by its human rights organs. The principle of inclusivity would also dictate the requirement that these focal points be involved in the entire court proceedings concerning their states. This is important in order to ensure that they understand what is expected in the eventual implementation process.102

An alternative mechanism in this regard would be the National Human Rights Institutions (NHRIs). Since these institutions already possess the personnel and are well informed on the work of AU bodies and in particular the Court’s decisions, and they also understand national stakeholders in the implementation process, they offer a better alternative as national coordinators of the implementation process of the Court’s decisions. Besides, NHRIs always work closely with civil society. Civil society is also a key source of information and advocacy in the implementation process. As indicated above, civil society is second in the number of cases it has lodged before the African Court. It therefore enjoys local legitimacy as they understand most of these disputes from their context and the best way of implementing the Court’s decisions. In fact, it is here suggested that civil society should form an integral component of the Court’s reporting system. As it is the case with shadow reporting to treaty bodies, civil society should be allowed to furnish the Court with information concerning the implementation of its decisions and the national contexts. Civil society could additionally voice their responses through the Pan African Governance Architecture as they comprise a huge element of its secondary membership. The involvement of civil society is likely to avert one of the major criticisms of the Court by member states of its failure to understand the context within which countries operate before giving fixed timelines on the implementation of its decisions.103 For example, the Malian government faulted the Court for failing to appreciate the countries cultural and religious contexts which hindered its implementation of the Court’s decision in APDF & IHRDA v Mali.104 Similarly, Kenya faulted the Court for failing to understand the complex nature of the land question in the country before making the resettlement order in the Ogiek case,105 while Rwanda lamented the failure of the Court to appreciate the political complexities that were at the time happening in the country.106 It is hoped that by allowing civil society to share its views on the implementation process early enough will help fill this gap.

A study by the African Court also suggests the utilisation of the Pan African Architecture on Governance - a platform for dialogue between the various stakeholders mandated to promote good governance and democracy in Africa107 - as an additional avenue for state reporting on their implementation of the Court’s decisions.108 The study also suggests the utilisation of the African Peer Review Mechanism (APRM) as another additional level of state reporting on the implementation of the Court’s decisions. This mechanism provides a rare opportunity which combines both experts and the political class to hold states to account for their implementation obligations.109 Indeed, since the peers in this country review process include heads of state, it could be hoped that they can exert the necessary political pressure on their peers to implement the Court’s decisions.

Effective utilisation of the doctrine of margin of appreciation is also key in establishing a working relationship between the Court and its member states in the implementation process. Already the African Court applies this principle by allowing states to determine the general and special measures to be taken in execution of judgments. For example, in the Ogiek case, the Court ordered Kenya “ to take all appropriate measures within a reasonable time frame to remedy all the violations established and to inform the Court of the measures taken ...”.110 This kind of flexibility adopted by the Court in the manner in which it drafts its judgments allows state parties some room to determine the best way of implementing their decisions. This flexibility can further be enhanced through the Court’s adoption of the practice that allows states to prepare and submit action plans to it. This approach is likely to further legitimise the implementation process as it pacifies the rigid political suspicions of the Court as an impostor and at the same time wins over local political will.

Limited capacity and resources at the national level has also been cited as another challenge in the Court’s relationship with member states in the implementation process. More so, some of the Court’s decisions have an impact of national budgetary allocation, while others require structural adjustments. These kinds of decisions are likely to take longer than the time ordinarily postulated by the Court. Yet, states parties end up being cited for non-compliance. Moreover, having acknowledged above that the working of the African Court is not well known, understood or written about, this is also the case with most state litigants. There have been instances of litigants referring to the African Court as an appellate court. A practice that has not boded well with the respective states parties. Tanzania has for instance condemned this and further challenged the jurisdiction of the African Court on the basis of decisions made by national courts. It is almost certain that this combative approach to the Court by member states is likely to compromise their eventual relationship in the implementation process. This has a general negative impact on their engagement with the Court and contributes to delays in implementation of its decisions.

4 Conclusion

The above assessment of the mechanisms and institutional framework of implementing the decisions of the African Court has established four key findings all of which point to the weaknesses inherent in the system. First, the institutional framework and relational mandate of the mechanisms involved in implementing the decisions of the African Court are not well established, understood and documented. This has contributed to the confusion among some litigants who often refer to the jurisdictional mandate of the Court to be an appellate one, a fact that has fuelled animosity between governments, in particular Tanzania and the Court. Second, the judges of the Court have failed to clarify, through practice and interpretation, the Court’s role in the implementation of its decisions. Yet, as an institution, the Court is riddled by numerous other challenges that hinder the effective implementation of its decisions. Third, the relationship between the Court and the AU policy organs is characterised by overriding institutional and political challenges. The partnership among the AU organs is also fragmented by a lack of clarity on how these institutions coordinate the implementation process. Fourth, the relationship between the Court and its member states involved in the implementation process is fragile and always defined by challenges that undermine effective implementation of the Court’s decisions. This kind of outcome of an assessment process requires concrete suggestions on the areas of reform that aim to strengthen the current framework. Firstly, the Court has to clearly define its role in the implementation process either under its rules of procedure or practice. The Court should also borrow some of the best practices like introduction of action plans, establishment of a monitoring unit within its registry and permanent staff dedicated to the implementation process. The Court can also adopt innovative monitoring strategies like joint monitoring with the concerned state parties, onsite visits and follow-up mechanisms in the post-judgment period. Secondly, the policy organs of the AU must step up to appoint permanent staff dedicated to the implementation process with a clear definition of how each organ coordinates with the other. These organs must also devise ways of exerting adequate peer pressure on member states that are reluctant to comply with the Court’s orders. The adoption of additional mechanism like country visits can also encourage member states to fully implement the Court’s decisions. Additional pressure should also be exerted on AU member states that have not ratified the African Court Protocol to do so, as well as encouraging member states to the Protocol to adopt the Article 34(6) declaration. Thirdly, member states must establish national focal points for coordination of the implementation process at the national level as well as with the Court and the AU policy organs.

1. AU Executive Council “Activity report of the African Court on Human and Peoples’ Rights” EX.CL/1258(XXXVIII) (2021) para 16 & Annex II https://www.african-court.org/wpafc/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/Activity-report-of-the-Court- January-to-December-2020.pdf (last accessed: 2021-06-30); The African Court Coalition (ACC) and Raoul Wallenburg Institute (RWI) Study on the implementation of decisions of the African Court on Human and Peoples’ Rights (2019) 2.

2. The Protocol was adopted on 10 June 1998 during the 34th Ordinary Session of the Assembly of Heads of States and Governments of the Organisation of African Unity (now the African Union) held at Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso. It came into force on 25 January 2004 after ratification by fifteen states. The 30 member states that have ratified the African Court Protocol include: Algeria, Benin, Burkina Faso, Burundi, Cameroon, Chad, Ivory Coast, Comoros, Congo, Gabon, The Gambia, Ghana, Kenya, Libya, Lesotho, Mali, Malawi, Mozambique, Mauritania, Mauritius, Nigeria, Niger, Rwanda, Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic, South Africa, Senegal, Tanzania, Togo, Tunisia and Uganda.

3. African Court “Basic Documents: Declaration featured articles https://en.african-court.org/index.php/basic-documents/declaration-featured-articles-2 (last accessed: 2020-06-11) .

4. Adjolohoun “A crisis of design and judicial practice? Curbing State disengagement from the African Court on Human and Peoples’ Rights” 2020 African Human Rights Law Journal 4.

5. It should be noted that the African Court Protocol does not expressly provide for this mandate. Some of these entities include: member states, the AU Assembly and the Executive Council.

6. Art 30 states that “[t]he state parties to the present Protocol undertake to comply with the judgment in any case to which they are parties within the time stipulated by the Court and to guarantee its execution”.

10. ACC conducted this forum on the side-lines of the 55th Ordinary session of the AfCHPR in Zanzibar, Tanzania from 29-30 November 2019.

11. Art 7 of the Protocol provides that the Court “shall apply provisions of the Charter and any other relevant human rights instruments ratified by the states concerned”. The African Charter expounds the range of human rights instruments to be used in the interpretation of the Charter. On its part, Article 60 of the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights allows the African Commission to draw inspiration from international law particularly from the provisions of various African instruments on human and peoples’ rights, the Charter of the United Nations, the Constitutive Act of the African Union, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, other instruments adopted by the United Nations and by African Countries in the field of human and peoples’ rights as well as from the provisions of various instruments adopted within the specialised agencies of the United Nations of which the parties to the Charter are members. This broadens the body of laws to which the Court can interpret while enforcing human rights on the continent.

1) If the Court finds that there has been violation of a human or peoples’ rights, it shall make appropriate orders to remedy the violation, including the payment of fair compensation or reparation.

2) In cases of extreme gravity and urgency, and when necessary to avoid irreparable harm to persons, the Court shall adopt such provisional measures it deems necessary.

21. Some of these include the Permanent Representatives Committee and the Specialised Technical Committees.

23. African Court “Current judges” https://www.african-court.org/wpafc/current -judges/ (last accessed: 2021-02-03).

28. See for instance The African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights v Republic of Kenya (Application 006/2012) ACtHPR (26 May 2017) 68.

29. African Union “Decision on the activities of the African Court on Human and Peoples’ Rights” EX.CL/Dec.903(XXVIII) Rev.1 (2016).

30. African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights v Republic of Kenya (Application 006/2012) ACtHPR (26 May 2017). See presentation made by Moimbo Momanyi (Senior State Counsel) on the status of Implementation during a Consultative Forum on the Implementation of decisions of the African Court conducted by the ACC on the side-lines of the 55th Ordinary Session of the AfCHPR in Zanzibar, 29-30 November 2019.

33. African Court African comparative study on international and regional courts on human rights on mechanisms to monitor implementation of decisions/judgments (2019) 49.

34. African Court African comparative study on international and regional courts on human rights on mechanisms to monitor implementation of decisions/judgments African Court 50.

35. IACHR “Annual Report” (2019) 61 https://www.corteidh.or.cr/docs/informe2019/ingles.pdf (last accessed: 2021-02-04) .

40. Key informant interview, held online, on 27 July 2020. This is, however, changing. In the year 2018, the Court conducted a study towards a harmonised framework for implementation of decisions of the AU human rights organs. The AU policy organs are still considering this study.

50. AU Executive Council “Activity report of the African Court on Human and Peoples’ Rights” EX.CL/1204(XXXVI) (2019) para 59, available at https://www.african-court.org/en/images/Activity%20Reports/EN%20-%20EX%20 CL%201204%20AFCHPR%20ACTIVITY%20REPORT%20JANUARY%20-%20DECEMBER%202019.pdf (last accessed: 2021-02-02).

51. Council of Europe “Presentation of the Department” https://www.coe.int/en/web/execution/presentation-of-the-department (last accessed: 2020-06-11).

52. Department of Execution of Judgments of the ECHR https://hudoc. exec.coe.int/ENG#{%22EXECDocumentTypeCollection%22:[%22CEC% 22]} (last accessed 2020-06-11).

54. African Court African comparative study on international and regional courts on human rights on mechanisms to monitor implementation of decisions/judgments 22.

55. Art 21(2), Constitutive Act of the AU; African Union “The Permanent Representatives Committee” https://au.int/en/prc (last accessed: 2020-05-20).

59. ACHPR “Statement on the occasion of the African Human Rights Day 2019” https://www.achpr.org/news/viewdetail?id=204 (last accessed: 2020-06-11).

63. AU Assembly “Decision on the Specialised Technical Committee (STCS) - Doc. EX.CL/496 (XIV)” Assembly/AU/Dec.227(XII) adopted in January 2009.

64. AU Assembly “Decision on the Specialized Technical Committees Doc. EX.CL/666(XIX)” Assembly/AU/Dec.365(XVII) July 2011, para 3.

66. AU 35th Ordinary Session of the Assembly of States in January 2018; 2018 African Court Activity Report.

67. Activity Report of the African Court on Human and Peoples’ Rights, 1 January-31 December 2018 at 51 and 60.

78. Art 46, European Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms, 1950. This is an organ of the EU that comprise ambassadors from EU member states.

83. African Court African comparative study on international and regional courts on human rights on mechanisms to monitor implementation of decisions/judgments 25.

87. African Court African comparative study on international and regional courts on human rights on mechanisms to monitor implementation of decisions/judgments 26; Cyprus v Turkey Merits, App 25781/94, ECHR 2001-IV 731.

89. African Court African comparative study on international and regional courts on human rights on mechanisms to monitor implementation of decisions/judgments 30.

91. African Court African comparative study on international and regional courts on human rights on mechanisms to monitor implementation of decisions/judgments African Court 32.

97. African Court African comparative study on international and regional courts on human rights on mechanisms to monitor implementation of decisions/judgments 47.

99. Task Force on the Implementation of the Decision of the African Court issued against the Government of Kenya in Respect of the Rights of the Ogiek Community of Mau and Enhancing the Participation of Indigenous Communities in the Sustainable Management of Forests Extension of Time, GN 4138 of 25 April 2019.

100. AU “Decision on the 2016 Activity Report of the African Court on Human and Peoples’ Rights Doc EX.CL/999(XXX)” EX.CL/Dec.949(XXX), 30th Ordinary Session of the Executive Council 25-27 January 2017, Addis Ababa para 7.

101. Art 24, 2005 Additional Protocol to the ECOWAS Treaty of 1975. This is the Protocol establishing the Community Court of Justice (CCJ) as the judicial arm of the community.

102. African Court African comparative study on international and regional courts on human rights on mechanisms to monitor implementation of decisions/judgments.

105. Presentations and discussions held during a Consultative Forum on the Implementation of decisions of the African Court conducted by ACC on the side-lines of the 55th Ordinary session of the AfCHPR in Zanzibar, Tanzania, 29-30 November 2019.

106. Kwibuka “Why Rwanda Withdrew from AU Rights Court Declaration” The New Times (2017-10-13) https://www.newtimes.co.rw/section/read/221701 (last accessed: 2020-06-01).

107. Decision of the 15th Ordinary Session of the Assembly of African Union (AU) Heads of State and Government (AU/DEC.304 (XV) held in July 2010.

108. African Court African comparative study on international and regional courts on human rights on mechanisms to monitor implementation of decisions/judgments 106-107.