Japhet Biegon

LLD (Pretoria) LLM (Pretoria) LLB (Moi)

Extraordinary Lecturer, Centre for Human Rights, Faculty of Law, University of Pretoria; Africa Regional Advocacy Coordinator, Amnesty International

Volume 54 2021 pp 404-429

Download Article in PDF

The views expressed in this article are personal and do not in any way reflect or represent those of Amnesty International.

SUMMARY

Judicial arms of Regional Economic Communities (RECs) in Africa are today active adjudicators of human rights cases. Originally designed to mainly deal with cases regarding regional integration and trade, the courts or tribunals of RECs have in the last two decades received and determined a solid stream of human rights cases. This article concerns itself with the human rights practice of the East African Court of Justice (EACJ), a sub-regional court operating under the aegis of the East African Community (EAC). It examines the extent to which EAC member states have implemented and complied with the human rights decisions of the EACJ. It is located within and adds onto the relatively new body of literature on compliance with decisions of sub-regional courts in Africa. In six human rights cases in which the EACJ found a violation of the EAC Treaty, the analysis finds full or partial compliance in three. Although the sample of cases analysed is small, the article points to important insights on factors predictive of compliance. These include international pressure, quick resolution of cases by the EACJ and the system of governance or level of democracy and rule of law in member states. As the EACJ is only as strong as its parent organisation, a more active involvement of the EAC Council of Ministers in monitoring compliance with EACJ decisions is imperative.

1 Introduction

Judicial arms of Regional Economic Communities (RECs) in Africa are today active adjudicators of human rights cases. They have earned a place in supranational judicial protection of human rights. Originally designed to mainly deal with cases regarding regional integration and trade, the courts or tribunals of RECs have in the last two decades received and determined a solid stream of human rights cases, a practice and trend that has been celebrated and frowned upon in almost equal measure.1 The African continent is home to more than eight RECs, but three of these are the most prominent: The East African Community (EAC); the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS); and the Southern African Development Community (SADC).2 It is also the judicial arms of these three that have established a distinct profile in the protection of human rights. This article broadly concerns itself with the human rights practice of the East African Court of Justice (EACJ), a sub-regional court operating under the aegis of the EAC.

Scholarship on the human rights practice of sub-regional courts has predictably evolved alongside the progression of the courts themselves. Three overlapping phases may be identified. Legal doctrinal analyses of the mandate of these courts to determine human rights cases predominated the first phase.3 This initial focus is not surprising. Except for the ECOWAS Court of Justice (ECCJ), sub-regional courts do not have an explicit mandate to adjudicate human rights cases. That they nevertheless do so has attracted some scholarly attention, and much more. Audacious if controversial human rights decisions have also triggered mounting state-led political backlash. This kind of pressure has significantly changed the landscape of sub-regional courts’ operating environment. The now defunct SADC Tribunal suffered the most severe and crippling effects. Political backlash led to suspension of its functions and eventual disbanding.4

The second phase of human rights scholarship on sub-regional courts saw the emergence of backlash studies,5 which have now spread to cover similar experiences of other international human rights bodies in Africa.6 Even though the threat of political backlash continues to hover over them, sub-regional courts remain undeterred in entertaining human rights cases. As the jurisprudence and dockets of the courts have increased, the attention of scholars has in the third phase naturally turned to the ever-lingering questions about implementation and compliance.7

This article is located within and adds onto this relatively new body of literature on implementation or compliance with decisions of sub-regional courts in Africa. It examines the extent to which EAC member states have implemented and complied with the human rights decisions issued against them by the EACJ. It builds upon a baseline survey and a policy study conducted by the East African Law Society (EALS) in a two-year policy research project supported, technically and financially, by the Regional Africa Programme of the Raoul Wallenberg Institute of Human Rights and Humanitarian Law (RWI).8 The survey tracked and documented the implementation of 109 decisions issued by the EACJ during the period 2005-2018. These decisions cover a relatively wide range of themes, including trade, immigration, human rights, and environmental issues.9

The dataset compiled by the EALS is the most comprehensive thus far on the extent to which decisions of the EACJ have been implemented. It presents new empirical evidence as well as important insights on the impact of the EACJ. This article filters out human rights cases from this dataset and examines their implementation in more detail. The article is structured as follows. After this introduction, section 2 provides an overview of the design and evolution of the EACJ as well as its practice relating to human rights. Section 3 begins by making some conceptual clarifications regarding the notions of implementation and compliance. It then examines the extent to which EACJ human rights cases have been implemented and complied with. In section 4, the article interrogates some of the factors that affect or influence the degree of state implementation and compliance. The final section draws the article to a conclusion.

2 The East African Court of Justice

The EAC is a REC that brings together six neighbouring states in the Eastern Africa region: Burundi, Kenya, Rwanda, South Sudan, Uganda, and Tanzania. It was established in 1999 by Kenya, Uganda, and Tanzania in a second attempt at regional integration. These three founding countries were previously members of an older version of the EAC that lasted for a mere ten years between 1967-1977. The primary goal of the EAC is to foster regional integration and trade.10 However, like SADC and ECOWAS, the EAC has found itself increasingly engaging in human rights promotion and protection.11 The EACJ has engaged in human rights adjudication in this broader context, notwithstanding that it lacks an express mandate to do so. This section provides an overview of the design and evolution of the Court as well as its practice relating to human rights.

2 1 Design and evolution

The EACJ is one of the principal organs of the EAC. It is established under Article 9 of the 1999 Treaty for the Establishment of the East African Community (EAC Treaty).12 Its key mandate is to ensure compliance with the EAC Treaty through judicial interpretation and enforcement.13 The Court’s jurisdiction also extends to labour disputes involving the EAC and its employees,14 arbitration matters in which the parties have conferred it with jurisdiction,15 and requests for advisory opinions by EAC member states or its policy organs.16 The EACJ has concurrent jurisdiction with national courts in the interpretation of the EAC Treaty and other EAC laws.17 However, the EACJ retains overall supremacy and its interpretation takes precedence over those of national courts.18 This arrangement serves to ensure legal uniformity, certainty and harmony.19

The EACJ was inaugurated in 2001.20 It had a single chamber in its original design. An amendment to the EAC Treaty that came into force in March 2007 created a second chamber.21 Its current structure comprises of the First Division and the Appellate Division.22 The First Division has original jurisdiction to hear and determine cases.23 The EAC Treaty allows up to a maximum of ten judges for the First Division, although is has been traditionally comprised of six.24 The Appellate Division has five judges, half the number allowed in the First Division.25 It sits to determine appeals from the First Division on points of law, jurisdiction and procedure.26

The EACJ judges are nominated by their respective countries and appointed to office by the EAC Summit,27 which is composed of all the heads of state of member states. The retirement age for the judges is set at 70 years, and they can only hold office for a single non-renewable term of seven years.28 The Court has since inception been based in Arusha, Tanzania. However, Arusha is not considered its permanent seat, as the EAC Summit is yet to formally make that determination as required of it by the EAC Treaty.29 The President of the EACJ (who is also the head of the Appellate Division) and the Principal Judge (head of the First Division) are based in Arusha. The rest of the judges are based in their respective home countries and periodically travel to Arusha to attend scheduled sessions.

The EACJ has established registries in each of the EAC member states and litigants need not travel to Arusha to file cases. In this context, cases may be lodged at the EACJ by member states, the EAC Secretary General, and legal and natural persons resident in any of the member states.30

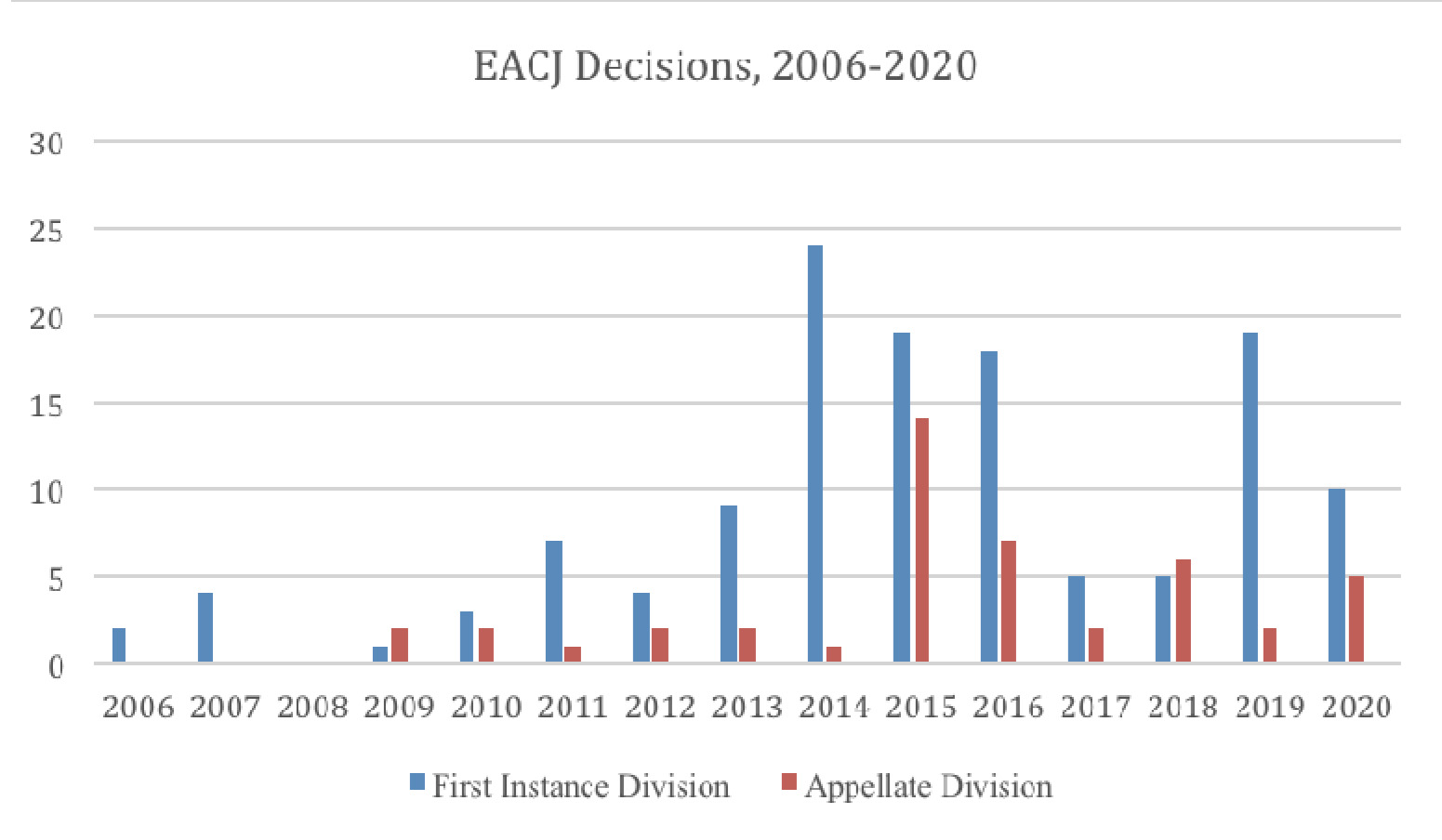

The EACJ had a slow start. It received its first case in 2005,31 about four years after it opened its doors. At the end of its first decade in 2011, the Court had rendered fourteen judgments, 29 rulings and one advisory opinion.32 In the second decade, the number of cases streaming into the EACJ has rapidly increased. The Court now handles an average of 40 matters and issues slightly more than ten judgments and rulings in a year.33

2 2 Human rights mandate

The EAC Treaty grants the EACJ a reasonably broad mandate and jurisdiction. Yet, if there is anything unique about the Treaty, it should be that it openly denies the Court the express authority to deal with human rights cases. Article 27(2) provides that “[t]he Court shall have such other original, appellate, human rights and other jurisdiction as will be determined by the Council at a suitable subsequent date”. It adds: “To this end, the Partner States shall conclude a protocol to operationalize the extended jurisdiction”. The EAC Treaty essentially envisages the possibility of the EACJ to exercise a human rights mandate, but not immediately. Rather, from a vaguely defined future date and contingent on the adoption of an additional protocol. Thus far, such a protocol has not materialised. The relevant EAC policy organs have remained unmoved by civil society advocacy on the matter. Even a judicial pronouncement by the Court itself has fallen on deaf ears.34

In November 2013, the EAC Summit gave the green light for a protocol extending the EACJ’s jurisdiction to be drafted. However, it directed that the protocol should only cover “trade and investment as well as matters associated with the East African Monetary Union”.35 On a human rights protocol, the Summit directed the Council of Ministers to “work with the African Union on this matter”.36 In September 2014, the EAC Sectoral Council of Legal Affairs put the matter to rest. It argued that the African Court on Human and Peoples’ Rights (ACtHPR), also based in Arusha but under the auspices of the African Union (AU), already provided an avenue for human rights to be litigated at the supranational level.37 It decided that for this reason, there was no need or urgency to extend EACJ’s mandate to explicitly cover human rights.38

The lack of an explicit human rights mandate has not deterred the EACJ from admitting and determining human rights cases. It has innovatively interpreted the EAC Treaty to allow it to consider such cases, albeit within a limited scope. The precedent was set in the case of James Katabazi v Secretary General of the EAC (Katabazi case).39 This case concerned violations of the right to a fair trial and freedom from arbitrary arrest and detention. The applicants, Ugandan nationals, were charged with treason and related offences. As soon as they were granted bail by the High Court, military officials surrounded the High Court, thwarted the preparation of the bail documents, and rearrested the applicants. They were then taken to a military court where they were charged with the same offences and subsequently remanded in prison. The actions of the military were successfully challenged in the Constitutional Court, but the state still defied the order for the release of the applicants. They moved to the EACJ.

At the EACJ, the Ugandan government argued that the sub-regional court lacked jurisdiction to determine the matter because it concerned alleged human rights violations. The EACJ rejected that argument and held that it could exercise jurisdiction as long as a matter is based on a provision of the EAC Treaty and notwithstanding that it concerns a human rights violation.40 It made reference to, inter alia, Articles 6(d) and 7(2) of the EAC Treaty. Article 6(d) provides in part that one of the fundamental principles of the EAC is “recognition, promotion and protection of human and peoples rights in accordance with the provisions of the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights”. Under Article 7(2), member states have undertaken to “abide by the principles of good governance, including adherence to the principles of democracy, the rule of law, social justice and the maintenance of universally accepted standards of human rights”. The EACJ proceeded to rule that the impugned actions of the Ugandan government violated the principles contained in Articles 6(d), 7(2) and other relevant provisions.

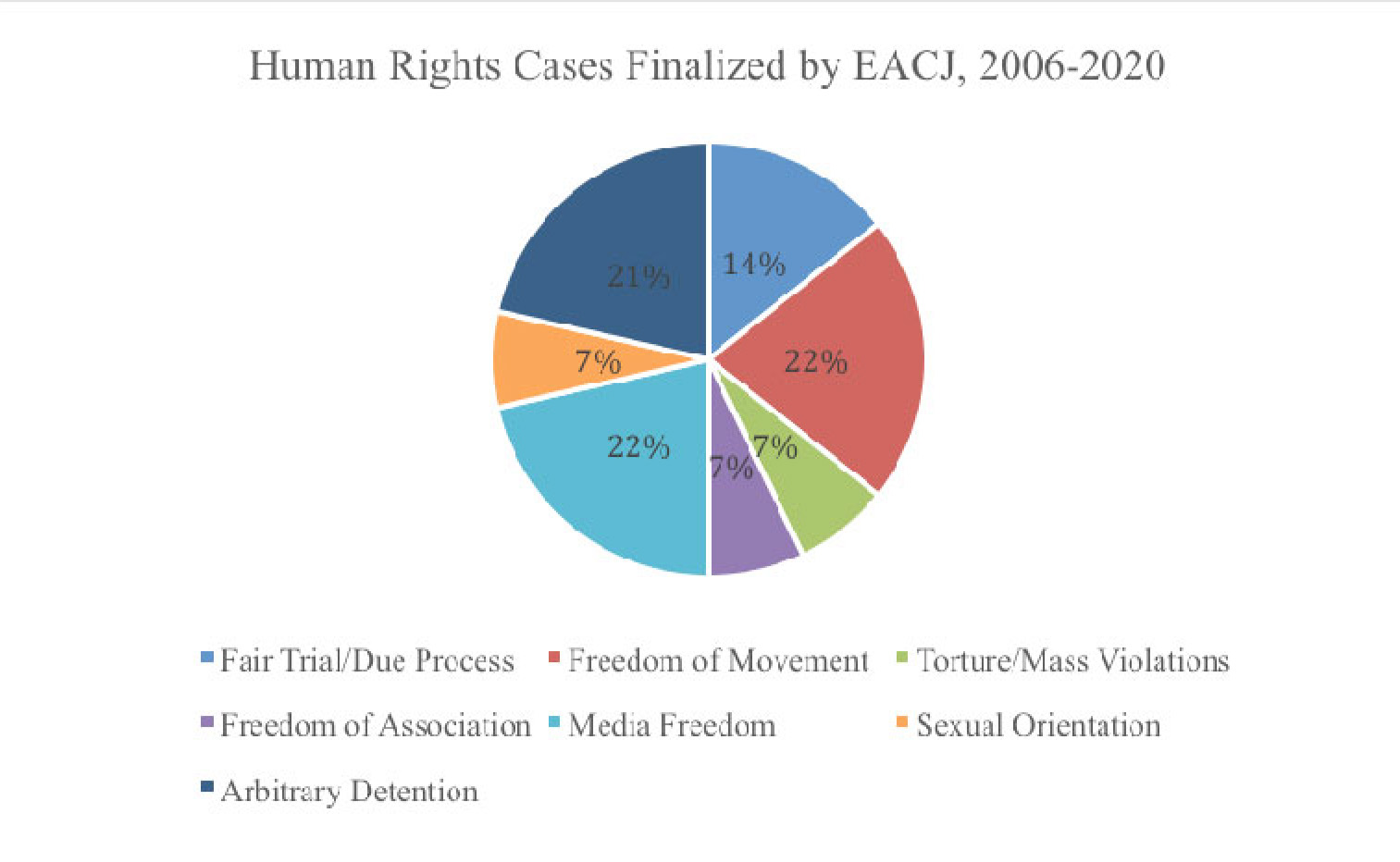

The Katabazi case opened the door for more human rights cases to be filed. Indeed, the EACJ has in subsequent cases gone further to hold that it would treat the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights (ACHPR) as a legitimate source of law for purposes of interpreting state obligations under Articles 6(d) and 7(2) of the EAC Treaty.41 The EACJ has effectively become a forum for supranational human rights adjudication.42 As at the end of July 2020, the EACJ had finalised fourteen cases that explicitly dealt with human rights.43 Each of these cases concerns multiple alleged human rights violations. When organised according to the most prominent concern they raise, it becomes clear that most cases relate to three themes: media freedom (22 per cent);44 freedom of movement (22 per cent);45 and arbitrary detention (21 per cent).46 The rest of the cases deal with the right to fair trial or due process,47 freedom of association,48 mass violations, including torture and extrajudicial killings,49 and the rights of sexual minorities.50 The human rights cases adjudicated by the EACJ as at July 2020 had originated from five of the six EAC members: Burundi, Kenya, Rwanda, Tanzania, and Uganda.

In the fourteen human rights cases finalised by the EACJ, it found a violation of the EAC Treaty in half of them (50 per cent). It found no violation in two and struck out two more at a preliminary stage. The latter cases had become moot at the time of their consideration. The three other cases were declared inadmissible because of a time limit tied to filing of cases by individuals and legal persons.

In the fourteen human rights cases finalised by the EACJ, it found a violation of the EAC Treaty in half of them (50 per cent). It found no violation in two and struck out two more at a preliminary stage. The latter cases had become moot at the time of their consideration. The three other cases were declared inadmissible because of a time limit tied to filing of cases by individuals and legal persons.The EAC Treaty provides that cases by individuals and legal persons should be filed “within two months of the enactment, publication, directive, decision or action complained of, on the absence thereof, of the day in which it came to the knowledge of the complainant, as the case may be”.51 The EACJ First Instance Division has taken a flexible approach in interpreting this provision. It has, for example, adopted the “continuous violations” principle to admit cases filed out of the time limit.52 The Appellate Division has on the contrary adopted a rigid approach that has seen it reverse the progressive decisions of the First Instance Division.53 This stance has been rightly criticised.54

Enabling treaties or rules of procedure of other international human rights bodies are either silent or provide a six-month time limit.55 The limit in the EAC Treaty is deemed too short. Its validity was challenged before the EACJ in the case of Steven Deniss.56 The applicant argued that the rule hindered access to justice, not just for him but also for many other victims of human rights violations. The EACJ declined to tinker with the rule lest it engaged in express law making. However, while it found that the rule is “neither strange nor outlandish”,57 the EACJ nonetheless recommended that it should be amended so that it applies to all parties who have access to the Court, not just individuals and legal persons.

3 Implementation and compliance with EACJ decisions

Implementation and compliance with decisions of international courts is a mark of their effectiveness and impact. For this reason, the EAC Treaty is unequivocal that the decisions of the EACJ are binding. It imposes an obligation on states to accept, implement and comply with EACJ decisions. Article 38(2) provides that “[a] Partner State or the Council shall, without delay, take the measures required to implement a judgment of the Court”. The EAC Treaty also requires states to act in good faith during the pendency of a case. In this context, states are expected to “refrain from any action which might be detrimental to the resolution of the dispute or might aggravate the dispute”.58 This also implies an obligation to comply with any interim orders issued by the Court. Interim orders have in this regard “the same effect ad interim as [final] decisions of the Court”.59

This section examines if and to what extent the above provisions are translated into practice. It begins by making some conceptual clarifications regarding the notions of implementation and compliance. It then turns to examine what happens to EACJ human rights decisions in the post-adjudication phase. Although the EAC is enjoined in almost all cases before the EACJ,60 the focus in this section is on the actions or omissions of member states. They are the primary duty bearers in matters of human rights and are ultimately responsible for implementing EACJ decisions.

3 1 Conceptual issues and clarifications

Implementation and compliance are sister concepts that are often used interchangeably in the literature. However, they have different meanings. On the one hand, implementation refers to the action of taking steps or putting measures in place to give effect to a decision of an international court or quasi-judicial body. For instance, if a decision of the EACJ requires government ‘x’ to reform or revise its law on a specific issue, implementation may entail introducing a bill in parliament to remove the offending provisions, and if necessary, replace them with acceptable clauses. Implementation cannot possibly happen without a conscious or deliberate decision. Compliance, on the other hand, refers to the alignment between the factual situation at the domestic level and a decision of an international judicial or quasi-judicial body. In other words, compliance is “a state of conformity or identity between an actor’s behaviour and a specified rule”.61 In the example above, compliance would be achieved if, at the end of the legislative process, the revised law satisfies the exact demands of the EACJ.

A clear distinction, then, is that implementation is a process while compliance is the outcome of that process. However, this simple distinction potentially masks some other complex or nuanced realities. For one, it is not guaranteed that implementation will lead to compliance, although it is a critical step in that direction. Indeed, compliance may be realised independently of implementation. It may be the result of sheer coincidence, change in circumstances or another neutral factor, and not the deliberate action of the concerned government. In the example above, if a new government comes to power in country “x” through a democratic process or some other means, it may introduce wide-ranging legal reforms as part of breaking with the past or charting a new trajectory for the country. The relevant law may thus be revised, but within a political context that has nothing or little to do with the decision of the EACJ. A causal relationship between the EACJ decision and the revised law may thus be difficult to establish although the decision would have been complied with in full. Scholars have aptly termed this kind of turn of events as “situational” or “sui generis” compliance.62

By design and necessity, studies or assessments of compliance usually capture the state of play at a particular point in time. Some form of categorisation of compliance is thus needed to control accuracy and reliability. A common approach is to understand compliance as running along a sliding scale, from “non-compliance” to “full-compliance”, and with ‘partial compliance” or “pending compliance” falling somewhere in the middle.63 The Inter-American Commission on Human Rights is particularly famous for using this typology.64 Full compliance refers to instances where the state has implemented all the remedial orders of an international court. Partial or pending compliance occurs when implementation is ongoing, and the state has complied with only some of the remedial orders. Non-compliance is recorded if no action whatsoever has been taken. This study adopts this typology, although as discussed below, it has some inherent shortcomings.

There are divergent opinions on the utility and appropriateness of partial compliance as a standalone category. One of the qualms with this category is that it effectively gives credence and weight to instances of non-compliance.65 Those advancing this critique see compliance in binary or dichotomous terms; at any one time, a state has either complied or not. There is no middle ground. Others find problems with the concept of partial compliance from a different angle. They argue that two states responding to similar sets of remedial orders may both be said to have partially complied even if their respective implementation measures are drastically different in both substance and meaning for the victims.66 The category thus fails to take into account the actual efforts of different states and instead lumps them together.

To address shortcomings of partial compliance, Hillebrecht has proposed an alternative concept she calls “aggregate compliance’, which takes into account a country’s performance on each remedial order in a single case, but also at the structural and aggregate levels.67 On their part, Hawkins and Jacoby have disaggregated partial compliance into several discrete forms, including “slow motion compliance”.68 These different conceptions of compliance point to the fact that categorisation remains “contentious, because implementation is not a static, but a dynamic process”.69

Compliance and implementation are closely related to two other distinct concepts that are important in a study of this nature: effectiveness and impact. Effectiveness refers to the degree to which a judicial decision induces change in behaviour, improves the state of the underlying problem or achieves its inherent policy objectives.70 Impact may be either direct or indirect. Direct impact is directly linked to compliance. It relates to whether a state has complied with a judicial decision, be it to make legislative changes or pay compensation.71 Indirect impact is different. It refers to “the manifold ways in which international human rights law may have an effect on prevailing discourses, in changing attitudes and thinking, in raising awareness, and the like”.72

The level of compliance and implementation of a judicial decision may go hand in hand with its level of effectiveness and impact, but not always. A high level of compliance may not necessarily lead to improvement of the underlying situation that a decision seeks to address. As Raustiala and Slaughter note, “the sheer existence (or lack) of compliance may indicate little about international law’s impact on behaviour”.73 Consider this example. Assuming the EACJ decision against government “x” above requires it to change its law on public assemblies to remove a clause that compels citizens to seek authorisation before holding demonstrations and to replace it with a requirement for mere notification. Government “x” may fully comply with the decision by changing its law as demanded. In practice, however, relevant government authorities may still purport to grant permission for demonstrations, thereby converting a de jure notification regime to a de facto authorisation regime. This mismatch between law and practice would mean that the decision has a low rate of effectiveness or impact even if it has been complied with in full. In the next session, substantive examples of the interplay between implementation, compliance, effectiveness, and impact are discussed.

3 2 Status of implementation and compliance

It must be clarified from the onset that one of the methodological difficulties in assessing compliance with the decisions of the EACJ is the purely declaratory nature of its final orders. In human rights cases, the logical step to take after finding or declaring a violation is for the court to specify the measures that the concerned state must take to remedy the violation. However, the EACJ has not established the practice of formulating precise and targeted remedies. Although it considers itself as “a primary avenue through which the people can secure not only proper interpretation and application of the Treaty but also effective and expeditious compliance therewith”,74 the EACJ has adopted a narrow interpretation of the orders it can issue to remedy human rights violations. It has indicated that its jurisdiction is limited to issuing “declarations of illegality of the impugned acts, whether of commission or omission”.75 It has accordingly declined, for example, to order the release of arbitrary detained individuals.76

In three of the human rights cases that it found a violation, the EACJ articulated no remedy whatsoever. It only declared that the EAC Treaty had been violated. In two others, the remedy is vaguely framed. It is not obvious what the state must do to comply. In the last two cases, there is an attempt to formulate specific remedies. The inconsistency in articulation of remedies complicates any effort to categorise the cases for purposes of determining compliance. It is particularly difficult to differentiate between full and partial compliance, as this is dependent on a subjective interpretation on the full range of measures that may be needed to address the violation. A case of full compliance in one study may be classified as partial compliance in another. In the discussion that follows, cases of full and partial compliance are discussed together to account for the difficulty in drawing clear distinctions. The discussion focuses on six of the seven human rights cases in which the EACJ has found a violation of the EAC Treaty. The six cases involve four EAC member states: Burundi (2), Rwanda (1), Uganda (1), and Tanzania (2).

Compliance with the Mohochi case is not discussed for two reasons. First, the EACJ did not issue any substantive remedy in the case, although it found that the Ugandan government had violated the EAC Treaty as well as the rights of the applicant. Second, the EACJ did not find a structural issue linked to the violation suffered by the applicant that needed to be addressed by the Ugandan government. It is important to briefly recount the facts of the case to illustrate the logic of this point.

The applicant is a Kenyan lawyer and human rights defender. He flew to Uganda in April 2011. On arrival at Entebbe International Airport, he was refused entry. Instead, he was served with a notice declaring him a “prohibited immigrant”, confined at the airport, and deported back to Kenya a few hours later. He subsequently filed suit at the EACJ contesting his treatment at the airport and forceful return to Kenya. The EACJ accepted all his claims, except for the one alleging that a section of the Ugandan immigration law was inconsistent with the EAC Treaty and the East African Common Market Protocol. If the EACJ had accepted this claim, it would then have been necessary to trace whether the Ugandan government had addressed the violation and establish if the law had been revised in the period after the case.

3 2 1 Full and partial compliance

There are three cases that fall under the broad category of full and partial compliance: the Katabazi case, Burundi Press Law case, and Rugumba case. In only one of these, namely Burundi Press Law case, did the EACJ attempt to formulate a remedy, albeit a vague one. It is apposite to start the analysis with this case. Filed by Burundi’s umbrella professional body for journalists, the Burundi Press Law case challenged several provisions of the country’s Press Law 1/11 of 4 June 2013. The enactment of the Press Law was met with international criticism,77 as it introduced severe restrictions on media and press freedom. These included compulsory accreditation of journalists, prohibition on publishing certain categories of information, prior censorship of any films directed in the country, requirement for journalists to disclose sources of their information, and heavy fines for ill-defined offences. The applicant argued that the Press Law violated the rights to freedom of expression and press freedom. They asked the Court to order for the law to be repealed or for all the offending provisions to be amended.

The EACJ partly agreed with the applicant. It found two provisions of the Press Law to be inconsistent with Articles 6(d) and 7 of the EAC Treaty. First, it held that the prohibition of publication of certain categories of information, such as information on the stability of the Burundian currency or contents of reports of commissions of inquiry, did not meet the test of reasonability, rationality, and proportionality.78 Second, the EACJ held that the requirement for journalists to disclose their sources fell below the “expectations of democracy” and that policy objectives of the state could be met “without forcing journalists to disclose their confidential sources” or in “less restrictive ways”.79 As for the appropriate remedy, the EACJ declined to frame its order as articulated by the applicant because of the jurisdictional restriction placed on it under Article 27(1) of the EAC Treaty. Instead, it formulated a rather vague order that required Burundi to “take measures, without delay, to implement this judgment within its internal legal mechanisms”.80

The Burundian government did not appeal the decision. About a week before the EACJ decision was delivered, the Burundian Parliament adopted amendments to the Press Law. On 9 May 2015, Law 1/15 was enacted in what was a culmination of a process that had begun after the country’s Constitutional Court annulled sections of the Press Law in January 2014.81 Law 1/15 modified several provisions of the Press Law. It introduced a requirement for authorities to justify any refusal or cancellation of a journalist’s accreditation, provided for accreditation decisions to be challenged in court, inserted a clause providing for protection of sources, and removed the hefty fines for offences. On the issue of sources, the 2015 amendment provides that journalists are guaranteed the right to protect their sources. However, the original offensive provision in the 2013 Press Law was not explicitly repealed,82 leaving room for journalists to still be compelled to disclose sources. This specific amendment has thus been derided as “meaningless”.83 Law 1/15 did not also address the issue of content regulation. In this context, the 2015 amendment only brought the Press Law into partial conformity with the decision of the EACJ.

Burundi’s partial compliance with the EACJ decision did not result in any meaningful improvement of the factual situation of media freedom in the country. In fact, conditions deteriorated. There was an attempted coup in the country two days before the decision was issued. In response to the attempted coup, state security agents reportedly destroyed equipment and infrastructure belonging to three prominent private radio stations.84 In the years that have followed, a violent clampdown on journalists and media houses has obliterated any form of media independence in the country.85 In May 2018, another troubling law was introduced. Law 1/09 of 11 May 2018 amends the country’s criminal procedure code to, inter alia, allow government authorities to intercept electronic communication, block websites and seize computer data.86 The country’s ranking has dropped 17 spaces in the World Press Freedom Index from position 143 in 2015 to 160 out of 180 countries in 2020.87

Of the two remaining cases, Katabazi was first in line. The facts of the case have been described above, but it is worth mentioning that the applicants only sought declaratory orders. This may partly explain why the EACJ did not issue any remedial orders in its judgment. However, since the main issue in the case was the alleged unlawful detention of the applicants, it should follow that compliance with the decision would obviously entail their release. In this context, the case has been fully complied with. Indeed, as soon as their lawyers announced that they would be filing suit at the EACJ, some of the applicants were released.88 With the passage of time, all the remaining applicants were also released. There is anecdotal if circumstantial evidence to suggest that the Katabazi case may have influenced the Ugandan military to generally exercise restraint in subsequent treason cases.89 However, the trial of civilians in military courts has continued long after the Katabazi case.90

The Rugumba case concerned the arrest and incommunicado detention by the Rwandan government of Seveline Rugigana Ngabo, a high-ranking military officer in the country’s defence force. When the suit was filed in November 2010, he had already spent four months in detention and had not been brought before a court of law. His family had also not been given information about his whereabouts or the location of his detention. Ngabo’s elder sister, Plaxeda Rugumba, approached the court seeking a declaration that her brother’s arrest and incommunicado detention violated Articles 6(d) and 7 of the EAC Treaty. The EACJ issued its judgment in December 2011, wherein it found that the applicant had established a violation of the EAC Treaty. The Rwandan government appealed the decision. It raised questions relating to the EACJ’s jurisdiction and admissibility of the case, all of which were dismissed.91

The Rugumba case triggered some level of state compliance with EAC Treaty obligations even before it was concluded, although in the long run the underlying human rights violation persisted.92 On 21 January 2011, slightly over two months after the case had been filed at the EACJ, the Rwandan government produced Ngabo in a military court for the first time. The government applied for his “preventive detention” at this instance. About a week later, on 28 January 2011, he was back in the military court for a ruling on the government’s application. The court ruled that his detention prior to being produced in court was “irregular”, but it nevertheless proceeded to regularise and extend the detention. Throughout 2011, the military court kept on extending his detention after every 30 days.93 The EACJ expressly declined to comment on this practice in its decision and chose instead to remind the Rwandan government that according to its laws, prevention detention can only last for a year and no more.94 Ngabo’s pre-trial detention continued even after the expiry of the one-year period. His trial had begun just before the EACJ decision was issued and in July 2012 he was sentenced to nine years in prison for endangering state security and inciting violence.95 The appeal process continues.

3 2 2 Non-compliance

Three cases of non-compliance are discussed in this sub-section in the chronological order in which they were issued: the Rufyikiri case, Tanzania Media Law case, and Mseto case. The Rufyikiri case concerned the plight of Isidore Rufyikiri who was at the time of filing the case the President of both the Burundi Bar Association (BBA) and the Burundi Centre for Arbitration and Conciliation (CEBAC). Three separate but intertwined events converged in 2013 culminating in EALS bringing the case on behalf of Rufyikiri. First, he was arraigned in court on charges of corruption in his role as the President of CEBAC. The Prosecutor General of the Anti-Corruption Court later prohibited him from traveling outside of the country. Second, a governor of a province lodged an application with the BBA’s Bar Council for disciplinary proceedings against Rufyikiri. The application arose out of a letter that Rufyikiri had written to the governor concerning a client. The governor claimed that the letter contained defamatory statements. Third, the Prosecutor General of the Court of Appeal of Bujumbura made an application to the Court seeking Rufyikiri to be disbarred. The Prosecutor General claimed that statements made by Rufyikiri in a press conference in his capacity as the President of the BBA undermined “the rules, State security and public peace”.96

On 28 January 2014, the Court of Appeal acted on the application of the Prosecutor General and disbarred Rufyikiri. The Supreme Court later turned down his appeal against the disbarment, whereupon he instructed EALS to file the suit at the EACJ on his behalf. He claimed that his prosecution was malicious, disbarment unprocedural and the travel ban unlawful (as it was not sanctioned by a court of law). The EACJ held that Rufyikiri’s prosecution was proper in law. However, it held that due process of the law had not been followed in respect of the travel ban and disbarment. The EACJ declined to order for reinstatement of Rufyikiri to the roll of advocates or for the travel ban to be lifted. Instead, it issued a general order requiring the Burundian government to “take, without delay, the measures required to implement this judgment”.

Another issue that came up in the Rufyikiri case related to the role of the EAC Secretary General. In early 2013, the Secretary General had appointed a task force to investigate alleged violations of the EAC Treaty in Burundi. The task force was scheduled to visit Burundi to conduct the investigations, but the plan never materialised, partly because of Burundi’s lack of cooperation. In its judgment, the EACJ ordered the EAC Secretary to immediately operationalise the task force. It also ordered Burundi to allow the task force to undertake the investigative mission.

Burundi is yet to comply with any of the orders of the EACJ more than five years later. Rufyikiri remains disbarred and restrained from leaving the country.97 Similarly, the investigative mission has never taken place, either because of Burundi’s intransigence or lack of insistence on the part of the EAC Secretary General.98 As Lando has noted, “there has been no observable change in law or policy in Burundi which draws its origins to the decision of the EACJ in this case”.99

The last two cases, Mseto and Tanzania Media Law, concern freedom of expression, press freedom and access to information in Tanzania. In the Mseto case, the applicants are respectively the editor and publisher of Mseto, a weekly newspaper in Tanzania. In August 2016, the Minister of Information issued an order suspending the publication of Mseto for a period of three years. The suspension seems to have been related to a story published in Mseto suggesting that a minister in the government had funded President John Magufuli’s election campaign using corruptly obtained monies. The applicants challenged the order. The EACJ found that the order had been issued unprocedurally and without cogent reasons:

By issuing orders whimsically and which were merely his ‘opinions’ and by failing to recognize the right to freedom of expression and press freedom as a basic human right which should be protected, recognized and promoted in accordance with the provisions of the African Charter, the Minister acted unlawfully.100

In a departure from its settled practice and jurisprudence, the EACJ in the Mseto case issued a direct and targeted order. It ordered the Tanzanian government to “annul the order forthwith and allow the applicant to resume publication of Mseto”.101 The Court reasoned that “an unlawful action must be followed by an order taking the parties to the status quo ante”,102 and as such, it saw “no difficulty in ordering the resumption of the publication of Mseto as prayed”.103

The Tanzania Media Law case challenged several provisions of the Media Services Act 120 of 2016, which came into effect in the country on 16 November 2016. The applicants raised concerns similar to those that had been raised in the 2013 Burundi Press Law case. They specifically challenged provisions of the law relating to regulation of the content of news, mandatory accreditation of journalists, criminal defamation, and criminalisation of publication of news and rumours. They also contested the absolute powers granted to the relevant government authorities to regulate the media industry. The EACJ found that most of the impugned provisions were broad and imprecise such that journalists and citizens could not be able to tell what kinds of conduct were prohibited under the law. It also found that the law imposed unjustified and disproportionate limitations on freedom of expression, press freedom and access to information. The EACJ ordered the Tanzanian government to take “such measures as are necessary to bring the Media Services Act into compliance with the Treaty for the Establishment of the East African Community”.104

In both Mseto and Tanzania Media Law, the government filed a notice of appeal but then failed to institute the actual appeal. The respective applicants proceeded to successfully apply for the notices of appeal to be struck out in June 2020.105 More importantly, the Tanzanian government has not complied with any of the orders of the EACJ in the two cases. The suspension of Mseto expired in August 2019, but even so, its publication could not resume because the Registrar of Newspapers argued that he could not issue a license while a notice of appeal was still pending at the EACJ.106 The suspension has persisted even after the notice of appeal was struck out in June 2020. In relation to the Media Services Act, the government has sent mixed signals. In March 2019, the Attorney General unequivocally said in a private meeting with a human rights group that the government would not comply with EACJ decisions.107 However, the Minister of Information shortly thereafter indicated in public that the government was considering the possibility of revisions.108 However, no concrete or visible steps have thus far been taken towards amending the law.

After the decisions of the EACJ in Mseto and Tanzania Media Law, attacks on freedom of expression and press freedom have greatly escalated. Even as Mseto remained suspended, more media outlets were fined, suspended or closed for publishing reports of human rights violations and the state of the country’s economy.109 More recently, media outlets have been punished with suspension for their coverage of the government’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic.110 Many cases of arbitrary arrests, intimidation, judicial harassment and enforced disappearances of journalists have also been documented in the last five years.111 Tanzania is ranked 124th out of 180 countries in the 2020 World Press Freedom Index.112 It has fallen 53 places since 2016, the steepest by a country during the same period.113

4 Determinants of implementation and compliance

The sample of cases analysed in this study is very small and any broader or generalised conclusions should be cautiously drawn. However, it is noteworthy that some of the findings here tally well with the results of the larger EALS policy study. For one the EALS study found that some level of implementation had taken place in 47 per cent of the cases in which implementation was required.114 The present study has recorded partial and full compliance in 50 per cent of the human rights cases in which some form of implementation was expected, a result that more or less corresponds with that of the EALS study. The results of this analysis also reveal that the compliance rate within the EAC is lower when compared with the compliance rate within ECOWAS. A 2013 study of compliance with the human rights decisions of the ECOWAS Court of Justice found a compliance rate of 66 per cent.115

Another important finding of the EALS study is that most cases in which the EACJ issued pecuniary orders have been implemented.116 The study notes that “EAC Partner States are more willing to pay when at fault as opposed to taking substantive steps to remedy ... violation of human rights or the rule of law”.117 In other words, it seems monetary orders are low hanging fruits that states readily pick without breaking a sweat. This trend is certainly encouraged by the fact that the EAC Treaty specifically addresses how orders of pecuniary nature should be implemented. Article 44 provides that “[t]he execution of a judgment of the Court which imposes a pecuniary obligation on a person shall be governed by the rules of civil procedure in force in the Partner State in which execution is to take place”. The present study could not test in detail whether the general trend seen in relation to implementation of pecuniary orders is applicable to human rights cases.

None of the human rights cases examined contain orders for monetary compensation for the violations addressed in those cases. The EACJ has also consciously avoided granting the costs of litigating human rights cases to the successful applicants, choosing instead to treat most of them as public interest cases.118 The thinking of the EACJ in the Mohochi case is instructive in this context. In declining to grant the applicant the costs of the suit, it observed as follows:

We believe that in the filing and prosecution of this Reference the Applicant’s objective was to highlight, contest and cause resolution to an issue of regional concern rather than to seek material restitution, for his six hour ordeal, from the Republic of Uganda. We think he has achieved that. It is our belief also that the physical and emotional distress he was subjected to, while tucked away and chilling unnecessarily at Entebbe International Airport, stung the human rights activist in him into seeking to prevent it from happening to another citizen of a Partner State. We would hope he has achieved this or, at any rate, made his contribution to its achievement. Finally, we have no doubt that the issues raised and determined in this Reference will enrich and benefit Community jurisprudence, courtesy of the Applicant. In view of the foregoing, we find that this Reference qualifies as a public interest and a fitting one where each party should bear their costs.119

A critical issue that often arises in studies of this nature relates to the mechanisms of enforcing compliance. Like any other international court, the EACJ does not have the power to cajole or arm twist states into compliance. It has dealt with the issue of non-compliance in the context of the Sebalu case in which the EAC was ordered to take quick action to extend the jurisdiction of the EACJ to cover human rights. After about a year, the applicant returned to the Court because the EAC had not paid its part of the costs of the suit as ordered, or taken any tangible steps towards extending the Court’s jurisdiction. The other respondent in the case, the Ugandan government, had already complied by settling its part of the bill. The applicant successfully asked the EACJ to cite the EAC Secretary General for contempt of court.

In its judgment, the EACJ observed that the object and purpose of Article 38 of the EAC Treaty on implementation of judgments is to ensure that “the orders of the Court are not issued in vain”.120 However, rather than sanction the Secretary General, the EACJ gave him an opportunity to purge the contempt. It remains unclear whether contempt of court proceedings are also applicable to member states and what sanction options are available to the Court if it finds a state in contempt. In the meantime, implementation of the Court’s decisions as the EALS study notes, depends largely on the political will of states.121 This means that the system of governance and the level of democracy and rule of law in a member state may have an influence on the stance that it takes in respect of EACJ human rights decisions.

It should not be perplexing that all three cases of non-compliance were issued at a time when the general human rights situation in the concerned countries was rapidly deteriorating. The Rufyikiri case came just days before an attempted coup in Burundi pushed the country to slide into authoritarianism. The partial compliance recorded in the Burundi Press Law case preceded the attempted coup. The two Tanzanian cases of non-compliance were issued after a new government had come to power in the 2015 general election. Commentators have noted that the reign of the new government has steadily shifted the state from a democracy to an autocracy.

Too much credence, however, should not be given to the system of governance as a factor predictive of compliance in the EAC region. All six EAC members perform rather poorly in major relevant scoring systems. In the 2020 Freedom in the World Index, for instance, only two countries (Kenya and Tanzania) fall under the category of “partly free”.122 The rest are considered “not free”.123 A defining factor for compliance in certain cases seems to be international pressure and global condemnation of the human right violation in question. This factor particularly played a role in the partial compliance seen in Katabazi and Burundi Press Law cases. In the latter, concerns by human rights groups from around the world were augmented by global leaders such as the United Nations’ Secretary General.124 International pressure may have also played in Tanzania’s indication that it would revise the 2016 Media Services Act in accordance with the EACJ decision, although it is now clear that the statement was less than genuine and was meant to deflect and pacify criticism.

A related factor to consider is whether the involvement of civil society in the EACJ human rights cases counts for something. Other studies have shown that civil society involvement in following up decisions of international human rights bodies is a relevant factor.125 Human rights groups file most of the human rights cases litigated at the EACJ. In the six cases analysed in section 3 above, two were filed by non-governmental organisations. The Rufyikiri case was filed by the EALS while the trio of Tanzania Media Council, Legal and Human Rights Centre and the Tanzania Human Defenders Coalition filed the Tanzania Media Law case. The rest of the cases had substantial involvement by civil society, although it is individuals or the directly affected entities that filed them.

No clear conclusions can be drawn from the sample of the cases analysed. Individuals filed the two cases where some compliance was recorded (Katabazi and Rugumba). A statutory body filed the third case: Burundi Press Law. In all the three cases, there was also broader publicity and pressure generated by civil society and the media. Civil society and other legal entities filed the three cases of non-compliance.

Another factor that seems to influence compliance at least in the short term is the mere filing of the case at the EACJ. In Katabazi and Rugumba, the concerned governments moved into action only after the cases had been filed. The two cases show, as Lando correctly observes, “at times the filing of suits may influence states to cease ongoing violations or take steps to comply with their human rights obligations”.126 The timing of the filing of a case is thus critical. This also means that the length of the time it takes to conclude a case at the EACJ may be relevant to sustaining the political will for compliance. The presumption is that the likelihood of compliance is relatively higher if a case is concluded within a short period of time and when the events leading to the filing of the case are still fresh.

Table 1: Length of time to finalise cases

Table 1 above shows that it takes an average of sixteen months for the EACJ to conclude human rights cases. The exact length of time ranges from a low of eight months in the Katabazi case to a high of 27 months in the Tanzania Media Law case. The computation of time seems to confirm the hypothesis that quick determination favours the possibility of compliance. On average, it took fourteen months for the EACJ to conclude the cases in which partial or full compliance was recorded while it took it 21 months for the cases in which non-compliance was recorded.

5 Conclusion

The EACJ has distinguished itself as a supranational human rights adjudicator. Using a mix of judicial activism and innovation, it has created a role for itself in the promotion and protection of human rights within the EAC. This article set out to determine the status of implementation and compliance with EACJ human rights decisions. Although the sample analysed is small owing to the relatively few numbers of human rights cases adjudicated by the EACJ, the article points to important insights on factors predictive of implementation and compliance. These include international pressure, quick resolution of cases by the EACJ and the system of governance or level of democracy and rule of law in member states.

In conclusion, it is important to recall that the EACJ operates within a broader institutional ecosystem. The Court is only as strong as its parent inter-governmental organisation. This is particularly relevant on the issue of implementation and compliance. In this context, there is much room for EAC’s improvement in its mechanisms for protection and promotion of human rights. One potential future direction of travel should be the active involvement of the EAC Council of Ministers in monitoring implementation and compliance with EACJ decisions. This role is implicit in several provisions of the EAC Treaty, but Article 14(3)(f) is specifically relevant. It mandates the Council to “consider measures that should be taken by Partner States in order to promote the attainment of the objectives of the Community”. This provision is broad enough to include considering whether member states have implemented and complied with EACJ decisions.

1. For a general discussion on the merits and demerits of human rights adjudication by the tribunals of RECs see Murungi and Gallineti “The Role of Sub-Regional Courts in the African Human Rights System” 2010 Sur International Journal on Human Rights 119.

2. The following are the five other major RECs in Africa: Arab Maghreb Union (UMA); Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa (COMESA); Community of Sahel-Saharan States (CEN-SAD); Economic Community of Central African States (ECCAS); and Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD).

3. Gathii “Mission Creep or a Search for Relevance: The East African Court of Justice’s Human Rights Strategy” 2013 Duke Journal of Comparative and International Law 249; Possi “Striking a Balance Between Community Norms and Human Rights: The Continuing Struggle of the East African Court of Justice” 2015 AHRLJ 192; Ebobrah “Critical Issues in the Human Rights Mandate of the ECOWAS Court of Justice” 2010 J Afr Law 1; Ebobrah “A Rights-Protection Goldmine or a Waiting Volcanic Eruption? Competence of, and Access to, the Human Rights Jurisdiction of the ECOWAS Community Court of Justice” 2007 J Afr Law 328; Alter, Helfer and McAllister “A New International Human Rights Court for West Africa: The ECOWAS Community Court of Justice” (2013) American Journal of International Law 737; Phooko “No Longer in Suspense: Clarifying the Human Rights Jurisdiction of the SADC Tribunal” (2015) PELJ 531.

4. The functions of the SADC Tribunal were de facto suspended in 2010 and de jure from 2012. The suspension was triggered by the political fallout that followed the decision of the Tribunal in a case concerning land rights in Zimbabwe. In 2014, SADC adopted a new treaty re-establishing the Tribunal. However, the re-established SADC Tribunal does not have the competence to receive cases from individuals. See Nathan “The Disbanding of the SADC Tribunal: A Cautionary Tale” 2013 Human Rights Quarterly 870.

5. Alter, Gathii and Helfer “Backlash Against International Courts in West, East and Southern Africa: Causes and Consequences” 2016 European Journal of International Law 293; Nathan 2013 Human Rights Quarterly; De Wet “The Rise and Fall of the Tribunal of the Southern Africa Development Community: Implications for Dispute Settlement in Southern Africa” 2013 ICSID Review: Foreign Investment Law Journal 45; Jonas “Neutering the SADC Tribunal by Blocking Individuals’ Access to the Tribunal” 2013 Human Rights Law Review 294.

6. See Adjolohoun “A Crisis of Design and Judicial Practice? Curbing State Disengagement from the African Court on Human and Peoples’ Rights” (2020) AHRLJ 1; Gerald “The African Court on Human and Peoples’ Rights: Mapping Resistance against a Young Court” (2018) International Journal of Law in Context 294; Biegon “The Rise and Rise of Political Backlash: African Union Executive Council’s Decision to Review the Mandate and Working Methods of the African Commission” EJIL Talk! Blog of the European Journal of International Law (2018-08-02) www.ejiltalk.org/the-rise-and-rise-of-political-backlash-african-union-executive-councils-decision-to-review-the-mandate-and-working-methods-of-the-african-commission (last accessed: 2020-08-15).

7. Adjolohoun “The ECOWAS Court as a Human Rights Promoter? Assessing Five Years’ Impact of the Koraou Slavery Judgment” 2013 Netherlands Quarterly of Human Rights 342; Lando “The Domestic Impact of the Decisions of the East African Court of Justice” 2018 AHRLJ 463.

8. Amol and Sigano The Study of the Status of Implementation of the Decisions of the East African Court of Justice and Level of Understanding of the Court Among Key Actors (2019).

9. See eg, Gathii “Saving the Serengeti: Africa’s New International Environmentalism” 2015-2016 Chicago Journal of International Law 386.

11. See Open Society Justice Initiative “Case Digests: Human Rights Decisions of the East African Court of Justice” (2013) east-african-court-digest-june-2013-20130726.pdf (last accessed: 2021-06-22).

19. East African Law Society v Attorney General of Kenya, (3 of 2007) EACJ (1 September 2008) (EALS case); Peter Anyang’ Nyong’o v Attorney General of Kenya (1 of 2006) EACJ (30 March 2007) (Anyang’ Nyong’o case)

21. This amendment was the result of political backlash against the EACJ, following its decision in the Anyang’ Nyong’o case. The amendments were unsuccessfully challenged in the EALS case. See Alter, Gathii and Helfer 2016 European Journal of International Law 293 300-306.

24. At the time of writing, the First Division had an even less judges. It was comprised of four judges from Burundi, Kenya, South Sudan and Uganda. Two judges who had retired had yet to be replaced.

25. At the time of writing, the Appellate Division had three judges after the tenure of two judges came to an end in June 2020. The remaining three judges are from Burundi, Rwanda, and Tanzania. See East African Court of Justice “Two Judges of the EACJ Appellate Division End Their Tour of Duties” www.eacj.org/?news=two-judges-of-the-eacj-appellate-division-end-their-tour-of-duties (last accessed: 2020-08-17).

29. EAC Treaty, Art 47 (“The seat of the Court shall be determined by the Summit”). Three countries (Kenya, Uganda, and Tanzania) have expressed interest in permanently hosting the EACJ. See Magubira “Tussle Heats Up Over Regional Court of Justice” The East African (2020-01-25) www.theeastafrican.co.ke/tea/news/east-africa/tussle-heats-up-over-regional -court-of-justice-1435524 (last accessed: 2020-08-20).

32. Ruhangisa “The East African Court of Justice: Ten Years of Operation (Achievements and Challenges)” Paper Presented During the Sensitisation Workshop on the Role of the EACJ in EAC Integration, Imperial Royale Hotel, Kampala, Uganda, 1-2 November 2011 www.eacj.org//wp-content/uploads/2020/04/EACJ-Ten-Years-of-Operation.pdf (last accessed: 2020-08-16).

34. Sitenda Sebalu v Secretary General of the EAC (1 of 2010) EACJ First Instance Division (30 June 2011) (Sebalu case). The Applicant in this case sought a determination on whether the long delay in extending the EACJ’s jurisdiction to cover human rights violated the EAC Treaty. The EACJ agreed and held that the delay contravened the principles of good governance as stipulated in Art 6 of the EAC Treaty. It ordered the EAC to take “quick action” to extend the Court’s jurisdiction as envisaged in Art 27 of the EAC Treaty.

35. Communiqué of the 15th Ordinary Summit of the EAC Heads of State, Kampala, Uganda, 30 November 2013, para 16.

37. Report of the 13th Meeting of the Sectoral Council on Legal and Judicial Affairs, EAC/SCLJA/16/2014, cited in Lando 2018 AHRLJ 467.

38. This reasoning failed to consider that direct access for individuals and NGOs to the ACtHPR is restricted. Under Art 34(6) of the ACtHPR Protocol, direct access to the ACtHPR for individuals and NGOs is conditional on states making a declaration accepting the competence of the Court to receive cases from individuals and NGOs. All the EAC member states have ratified the ACtHPR Protocol, except South Sudan. Tanzania and Rwanda initially made the Art 34(6) declaration but have since withdrawn it. Burundi, Kenya and Uganda have never made the declaration. In essence, the ACtHPR is not necessarily a viable and alternative supranational redress mechanism for residents of EAC.

39. (1 of 2007) EACJ First Instance Division (1 November 2007); (2007) AHRLR 119 (EAC 2007) (Katabazi case).

40. See also Democratic Party v Secretary General of EAC (Appeal 1 of 2014) EACJ Appeal Division (28 July 2015) para 55 (“It is obvious that once a matter involves the interpretation and application of the provisions of the Treaty, such matter falls ipso jure within the jurisdiction of the EACJ [jurisdiction ratione materiae, namely jurisdiction over the nature of the case and the type of relief sought]”).

42. While human rights actors have litigated actively before the EACJ, business actors have ironically eschewed it. See Gathii “Variation in the Use of Subregional Integration Courts Between Business and Human Rights Actors: The Case of the East African Court of Justice” 2016 Law and Contemporary Problems 37.

43. A ‘human rights case’ is here understood to mean a case in which there is an alleged violation of a specific human right of an individual or a group of people. In the context of the EAC Treaty, there is a tendency in the literature to refer to all cases that are based upon Arts 6(d) and 7 as human rights cases. However, some of these cases concern broader issues of rule of law. These issues are critical to the enjoyment of human rights at the domestic level, but rule of law is conceptually distinct from human rights. Some other cases filed under Arts 6(d) and 7 are directly linked to human rights because they, for instance, question the delay in extending the jurisdiction of the EACJ (Steven Deniss v Attorney General of Burundi (3 of 2015) EACJ First Instance Division (31 March 2017)) or the failure of member states to allow direct access to the African Court on Human and Peoples’ for individuals and non-governmental organisations (Democratic Party v Secretary General of EAC). It is best to categorise these cases as “human rights-related cases” as they deal with structural issues rather than infringement of the rights of specific individuals.

44. Burundi Journalists Union v Attorney General of Burundi (7 of 2013) EACJ First Instance Division (15 May 2015) (Burundi Press Law case); Media Council v Attorney General of Tanzania (2 of 2017) EACJ First Instance Division (28 March 2019) (Tanzania Media Law case); Managing Editor, Mseto v Attorney General of Tanzania (7 of 2016) EACJ First Instance Division (21 June 2018) (Mseto case).

45. Mohochi v Attorney General of Uganda (5 of 2011) EACJ First Instance Division (17 May 2013); Mbugua Mureithi wa Nyambura v Attorney General of Uganda (11 of 2011) EACJ First Instance Division (24 February 2014); East African Law Society v Attorney General of Uganda and Another (2 of 2012) EACJ First Instance Division (17 May 2013) (Walk to Work case). For a review of the jurisprudence of the EACJ on the right to movement see Nakule “Defining the Scope of Free Movement of Citizens in the East African Community: The East African Court of Justice and its Interpretive Approach” 2018 J of Afr Law 1.

46. Plaxeda Rugumba v Secretary General of the EAC (8 of 2010) EACJ First Instance Division (30 November 2011); Attorney General of Uganda v Omar Owadh Omar (Appeal 2 of 2012) EACJ Appellate Division (15 April 2013); East Africa Law Society v Attorney General of Uganda (3 of 2011) EACJ First Instance Division (4 September 2013) (Uganda Terror case).

47. James Katabazi v Secretary General of the EAC; East African Law Society v Attorney General of Burundi (1 of 2014) EACJ First Instance Division (15 May 2015) (Rufyikiri case).

48. Le Forum Pour le Renforcement de la Societe Civile (FORSC) v Attorney General of Burundi (12 of 2016) EACJ First Instance Division (4 December 2019).

49. Attorney General of Kenya v Independent Medical Legal Unit (Appeal 1 of 2011) EACJ Appellate Division (15 March 2012) (IMLU case).

50. Human Rights Awareness and Promotion Forum (HRAPF) v Attorney General of Uganda (6 of 2014) EACJ First Instance Division (27 September 2016).

51. EAC Treaty, Art 30(2). This provision is almost identical to Art 230 of the Treaty Establishing the European Community. It did not exist in the original EAC Treaty and was introduced in the 2007 amendment in reaction to the EACJ’s decision in the Anyang’ Nyong’o case.

52. See eg Independent Medical Legal Unit v Attorney General of Kenya (3 of 2010) EACJ First Instance Division (29 June 2011).

54. Possi “An Appraisal of the Functioning and Effectiveness of the East African Court of Justice” 2018 PELJ 14-18.

55. See eg, European Convention on Human Rights, Art 35(1); American Convention on Human Rights, Art 46(1)(b).

60. The practice of enjoining the EAC through its Secretary General in EACJ cases is based on the duty imposed on the Secretary to monitor member states’ compliance with Treaty obligations. See EAC Treaty, Arts 29 and 71(d).

61. Raustiala and Slaughter “International Law, International Relations and Compliance” in Carlsnaes, Risse and Simmons (eds) Handbook of International Relations (2002) 539.

62. Viljoen and Louw “State Compliance with the Recommendations of the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights, 1994-2004” 2007 American Journal of International Law 5.

64. See General Guidelines on the Follow-up of Recommendations and Decisions of the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, OEA/Ser.L/V/II.173, Doc 177, 30 September 2019, paras 24-25.

65. Abebe “Does International Human Rights Law in African Courts Make a Difference” 2016 Virginia Journal of International Law 550.

66. Hillebrecht “Rethinking Compliance: The Challenges and Prospects of Measuring Compliance with International Human Rights Tribunals” (2009) Journal of Human Rights Practice 362.

68. Hawkins and Jacoby “Partial Compliance: Comparison of the European and Inter-American Courts of Human Rights” 2010 Journal of International Law and International Relations 35.

70. Raustiala “Compliance and Effectiveness in International Regulatory Cooperation” 2000 Case Western Reserve Journal of International Law 393.

71. Viljoen “Exploring the Theory and Practice of the Relationship Between International Human Rights Law and Domestic Actors” 2009 Leiden Journal of International Law 179-180.

76. Hilaire Ndayizamba v Attorney General of Burundi and Another (3 of 2012) EACJ First Instance Division (28 March 2014); See also Plaxeda Rugumba v Secretary General of the EAC para 24.

77. See eg, “UN Chief ‘Regrets’ New Burundi Media Law Which May Curb Press Freedom” UN News (2013-06-06) www.bnub.unmissions.org/un-chief-‘regrets’-new-burundi-media-law-which-may-curb-press-freedom (last accessed: 2020-08-19); Defend Defenders “Burundi: Amend New Press Law” (2013-05-03) https://defenddefenders.org/2525/ (last accessed: 2020-08-19); Human Rights Watch “Burundi: Concerns About New Media Law” (2013-04-25) www.hrw.org/news/2013/04/25/burundi-concerns-about-new-media-law (last accessed: 2020-08-19).

81. Reporters Without Borders “National Assembly Passes New Media Law” (2015-03-10) www.rsf.org/en/news/national-assembly-passes-new-media-law (last accessed: 2020-08-19).

83. “Joint Submission to the Universal Periodic Review by Article 19, the Collaboration on ICT Policy in East and Southern Africa (CIPESA), the East Africa Law Society, the Pan African Lawyers Union (PALU) and the East and Horn of African Human Rights Defenders Project (Defend Defenders)” (2017-06-29) www.article19.org/data/files/medialibrary/38816/Joint-submis sion-to-the-Universal-Periodic-Review-of-Burundi-by-ARTICLE-19-and-others.pdf (last accessed: 2020-08-19).

84. “Joint Submission to the Universal Periodic Review by Article 19, the Collaboration on ICT Policy in East and Southern Africa (CIPESA), the East Africa Law Society, the Pan African Lawyers Union (PALU) and the East and Horn of African Human Rights Defenders Project (Defend Defenders)”.

85. See Bizimana and Kane “How Burundi’s Independent Press Lost its Freedom” The Conversation (2020-07-23) www.theconversation.com/how-burundis-independent-press-lost-its-freedom-143062 (last accessed: 2020-08-19).

86. CIPESA “A New Interception Law and Blocked Websites: The Deteriorating State of Internet Freedom in Burundi” (2018-07-11) www.cipesa.org/2018/07/a-new-interception-law-and-blocked-websites-the-deteriorating-state-of-internet-freedom-in-burundi (last accessed: 2020-08-19).

87. Reporters Without Borders “2020 World Press Freedom Index” www://rsf.org/en/ranking# (last accessed: 2020-08-19).

88. Candia and Ssempogo “Three PRA get Amnesty” New Vision www.newvision.co.ug/news/1173220/pra-amnesty (last accessed: 2020-08-19).

90. Human Rights Watch, Righting Military Injustice: Addressing Uganda’s Unlawful Prosecutions of Civilians in Military Courts (2011).

91. Attorney General of Rwanda v Plaxeda Rugumba (Appeal 1 of 2012) EACJ Appellate Division (22 June 2012).

92. See Human Rights Watch “We Will Force You to Confess”: Torture and Unlawful Military Detention in Rwanda (2017).

93. See eg, Karuhanga “Court Extends Rugigana’s Detention” The New Times (2011-09-2011) www.newtimes.co.rw/section/read/34591 (last accessed 2020-08-20).

95. “Military Court Hands Nine Years to Rugigana” The New Times (2012-07-26) www.newtimes.co.rw/section/read/55495 (last accessed: 2020-08-20).

105. The Managing Editor Mseto v Attorney General of Tanzania (3 of 2019) EACJ Appellate Division (2 June 2020) (Mseto Appeal); Media Council of Tanzania v Attorney General of Tanzania (Appeal 5 of 2019) EACJ Appellate Division (9 June 2020).

108. Shaban ‘Tanzania Commits to Reviewing Draconian Media Law’ Africa News (2019-04-05) www.africanews.com/2019/04/05/tanzania-commits-to-revie wing-draconian-media-law// (last accessed: 2020-08-20).

110. Reporters Without Borders “Tanzania Suspends Another Media Outlet Over its Covid-19 Coverage” (2020-07-10) www.rsf.org/en/news/tanzania-suspends-another-media-outlet-over-its-covid-19-coverage (last accessed: 2020-08-21).

115. Adjolohoun “Giving Effect to the Human Rights Jurisprudence of the Court of Justice of the Economic Community of West African States: Compliance and Influence” (LLD Thesis, 2013, University of Pretoria) 184.

118. Costs of the suit were granted in favour of the applicants in three cases: Katabazi, Rugumba and Mseto.

120. Sitenda Sebalu v Secretary General of the EAC (8 of 2012) EACJ First Instance Division (22 November 2013) para 52.